Behind the scenes at the new Purdey factory

The new Purdey factory in Hammersmith has been designed to take the company far into the future, without losing sight of the traditional values which made it famous in the first place, as Caroline Roddis discovers.

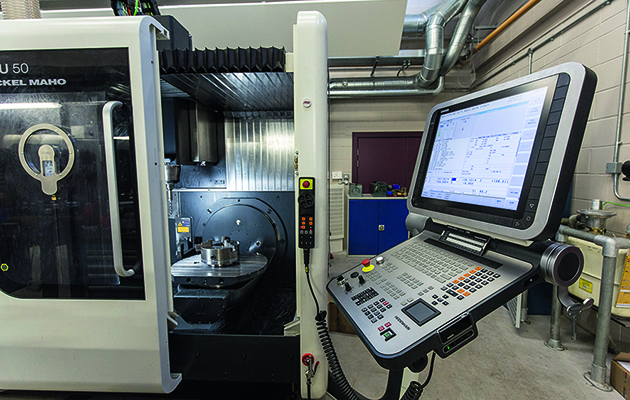

The new factory houses an impressive traditional workshop upstairs and a state-of-the-art machine shop downstairs

The new Purdey factory, which opened in June 2015, looks a bit like a Farrow & Ball version of the CERN supercollider. It’s part science lab, part artists’ workshop and part private members’ club. Chequered leather banisters and sepia-tinted pictures suddenly give way to orderly, well-lit rooms filled with hulking electromagnetic discharge machines or diligent craftsmen, and the entire thing is neatly balanced on top of an innovative 50 metre shooting range. But this juxtaposition of the traditional and the cutting edge is not just aesthetic, it is in fact a dichotomy at the heart of 21st century Purdey.

This is not something that has happened by accident. Despite being a poster boy for all that’s traditional in the shooting world, Purdey is now actively pursuing a programme of innovation and efficiency, much of which is being driven by technology.

Purdey has not lost sight of the importance of the traditional hand-made aspects of gunmaking

“Best gunmakers in the world”

“There’s a bit of a quiet revolution going on at Purdey,” says Laurie Bayliss, the firm’s production director and chartered engineer. “We’d like to regard ourselves as the best gunmakers in the world, and to live up to that reputation you’ve got to demonstrate you know your game and can take it forwards. The business has probably sat on its laurels for quite a long time.”

There is evidence of this revolution everywhere – even the clothing department has experimented with the launch of a spring/summer collection this year – but in the factory it is most obviously manifested in two key processes. The first is extracting knowledge from experienced craftsmen’s heads and quantifying or challenging it, allowing the company to build a strong set of scientific principles upon which to base its work. In the machine shop, for example, there is a V-spring testing rig that allows Purdey to determine the optimum combination of spring life versus spring force. This rig runs continuous cycles that exert pressure on up to four springs at once, allowing for a direct comparison of different types.

“Traditionally the guys upstairs would do this by trial and error,” comments Bayliss, referring to the fact that the machine shop is situated a floor below the craftsmen’s workshop. “We can do 40,000 cycles, then look at them and say, OK, the best one is 45 hardness Rockwell; a particular shape; a particular finish; then give this data to the craftsmen and tell them to make springs exactly like that. It’s more reliable this way.”

Purdey has not lost sight of the importance of the traditional hand-made aspects of gunmaking

Tech versus Tradition

The second process evident throughout the factory is streamlining, and it’s here that tensions can most easily arise. Although Bayliss states that development has increased exponentially in the last four years, even the use of CNC machines, introduced over 14 years ago, can still raise eyebrows.

“Sometimes customers will say ‘I don’t like that – why can’t you make it the old way, by forging a block of steel?’ We say that we can, but it would take about five years to produce a gun, and instead of £80,000 they’d be starting at £150,000-£200,000. We’d probably be able to make around 10 a year… the business might not have survived.”

Without CNC machinery and significant investment it could take five years to build a Purdey shotgun, which would then cost at least twice as much

It’s not just the customers who can be wary. There is also a definite split between the machine shop downstairs and the workshop upstairs, symbolised by the fact that the former uses metric measurements while the craftsmen work in imperial. While the latter benefit from the efficiencies created by the machines, they can also occasionally find them difficult to work with.

Tony Smith, a senior barrel-maker who was apprenticed at Purdey in 1972 and returned in 2011 after 25 years of self-employment, reflects on the company’s new direction. “It’s different now – there’s a lot more machining…. It’s good, as long as it’s right, which is not always the case unfortunately. A lot of the parts we get, they’re trying to get too close. We like something to play with: that’s not always the case and it causes problems.”

It was a reputation for precision in every department that made Purdey famous in the first place, such as making all its own tools

The new Purdey factory at home in Hammersmith

So has Purdey sold its soul in the pursuit of innovation? A walk around the new factory suggests otherwise. Having taken more than two years to rebuild from the underground up, the building has been expressly designed to provide the best possible environment for the 30 craftsmen and apprentices, and 10 machinists.

Although it would have been simpler to move to a new, purpose- built location, Purdey chose to stay in Hammersmith not only to preserve its tradition of London gunmaking (although the company has only been at Felgate Mews since 1979, it has been manufacturing in London for just over 200 years) but also to provide the best possible experience for customers and staff, the latter of whom have easy access to amenities and the Purdey shop. The customer experience has been particularly well designed, and the factory even contains a plush meeting room that has been dubbed the ‘Short Room’ thanks to its resemblance to the famous Long Room in Purdey’s South Audley Street building.

The new ‘Short Room’ at the Hammersmith site is a scaled down version of the famous Long Room at the South Audley Street headquarters

First-class investment

Factory rebuilds do not come cheap, but Purdey was able to aim for a best- in-class factory thanks to the support of its parent company, the Richemont Group. “It can invest well beyond the grasp of a Purdey-size business,” explains Bayliss. “That’s a fantastic position for us to be in, as we’ve got all that support and help to take us forward, but at the same time we want to be commercially viable, we want to push ourselves a bit.” The parent company, whose CEO can, endearingly, often be found toting rifles, also helps Purdey develop a competitive edge by allowing it to compare manufacturing processes with other companies in the group, such as Cartier.

Although as with many new builds there are improvements to be made, the factory is already delivering benefits. For example the spotless new shooting range allows the team to carry out testing and regulating without spending hours in the car driving to and from the West London Shooting School. Upstairs, meanwhile, better lighting and improved facilities let the craftsmen work to their full potential, while the new layout also allows them to bring more processes in house. These processes range from very accurately measuring complex shapes, to barrel-making, which is due to be done within the factory in the next year or so. The staff are clearly thriving in their new environment. This is crucial as, despite the advantages of the upgraded premises, it and the company’s future would be nothing without the Purdey team itself.

The new range incorporates a number of new features that enable more research and development

Quiet culture of innovation

A typical Purdey will spend 200 hours in the machine shop and more than 1,000 hours in the workshop, passing through the hands of expert barrel- makers, actioners, stockers, engravers and finishers along the way. Thanks to the lure of Purdey’s expertise and history however, the company has its fair share of atypical customers, whose orders can take far longer. Just a few of the guns on the shop floor, or waiting in the wonderfully enticing gun room to the side of it, are a .600 double rifle, an octagonal-barrelled .22 rifle (the type of which was last made around 80 years ago), and a 10 bore with both rifled and smooth barrels.

There has always been a quiet culture of innovation at Purdey, whether that’s creating its own tools to ensure it gets the best results, or pitching designs for engraving on special projects such as the Bicentenary trio.

This new push, then, can perhaps be seen as less revolution and more evolution, spurred on by new staff with 21st century skills seeking to augment those being practiced since the 19th.

In the past few years Purdey has acquired everyone from a first-class quality manager to the production engineer who built the V-spring test rig. And the engineer hasn’t stopped there. Not only is he currently working on a new rig that will put around 70,000 cartridges through a gun in four to five months to simulate years of heavy usage, something that will help Purdey develop a brand new gun, but he has also refined the pattern- plate process through the use of high- definition cameras. Down in the range they now shoot at a large roll of paper, which the camera photographs in order to capture every pellet hole. This is used to instantly calculate the exact centre and how many pellets are in the standard 30-inch circle, saving the testers a lot of time and effort – not to mention the need to continually whitewash the plate behind.

Teddy bear coffins lead the way

These innovations and the constant pursuit of knowledge contribute to a real science lab feel in the factory, and everyone gets involved. Laurie, for example, has worked on determining the best way to catch bullets in order to examine how they’ve passed through rifling: “We considered ballistic gel,” he says, “but I was told that teddy bear stuffing is the best thing, so I built a kind of wooden coffin about one-and- a-half foot square, filled it with stuffing and stuck three of them together…” The team shot at the teddy bear coffins and no bullets emerged, so Bayliss got stuck in: “I’ve never had to help a cow give birth, but in went my arm until I eventually found something that felt like a big hot tennis ball. When I unwrapped it from the ball of stuffing it was a perfectly clean bullet with no deformation, it had rifling perfectly etched into it, so I could read exactly how it had exited the barrel.”

Purdey states its aim is to not only secure its place at the top of the gunmaking world, but to ensure its factory lasts for another 200 years. Everything, from the positive atmosphere in the workshop to the innovation below, suggests Purdey will achieve this because of, rather than despite, the friction between maintaining tradition and embracing change. In any case, it may be a purpose built, state-of-the-art factory, but to anyone interested in shooting who’s lucky enough to walk through an unassuming door in Hammersmith, it’s more like an old-fashioned candy shop.