The countdown is on for The British Shooting Show – book tickets online today and save on gate price!

.17 Hornet calibre review

.17 Hornet calibre review: Rifle expert George Wallace investigates a baby centrefire that’s been a long time in development - the .17 Hornet.

.17 Hornet calibre review.

Most of us are now familiar with the .17 HMR (Hornady Magnum Rimfire) and its centre-fire predecessor, the .17 Remington.

And thank heavens the word has spread – this means I no longer have so many NGO members telling me that someone in their police firearms’ licensing department told them: “You don’t need a certificate for that; it’s only an airgun!”

There’s nothing new about .17 cartridges because some of the great names of American rifle building, cartridge design and varmint hunting were deeply involved immediately after the Second World War.

The idea behind the .17 was to reduce noise levels close to human habitation, and use a bullet that would not be prone to ricochet – both valid reasons that are still most appropriate in 21st century Britain.

The rifles were primarily intended for shooting Woodchucks.

The woodchuck appears in half a dozen subspecies of various sizes and can weigh anything from between three and about 15 pounds.

They are peculiarly tough little creatures with a physique described by Landis as: “A large, fat, ruggedly built squirrel with a heavy-set body, the general lines of which follow rather closely those of an alderman who has been on the public payroll for ten to 20 years.”

They are also quite capable of seeing off all but the most determined of dogs.

EXPERIMENTAL STAGES

Several of the experimental .17 cartridges were designed by C.S. Landis, the barrels rifled by P.O. Ackley and chambers cut by Charles Parkinson – all in a constant search to discover the best bullet weight, velocity and case capacity to achieve the desired end.

By 1950 the .170 Landis Woodsman seemed to be about the best of them, based on the Winchester 25-20 or R-2 Lovell case necked down to .17and with a 28-degree shoulder.

It drove a 25 or 30-grain bullet at 3,300 to 3,500 feet per second (fps).

It’s interesting to read that they tried constantly to use .22 Hornet or K-Hornet cases but could not get enough of the then-available powders into the case to produce the desired velocity within acceptable pressure limits.

However, Mr Ackley still reckoned the Hornet case was the perfect size to balance .17 calibre bullets for best potential accuracy.

THE RESULT

And so, finally, enter the .17 Hornet… a child of the 21st Century. Sixty-odd years later, and following the breakthrough in powder research which allowed the .17 HMR to achieve a previously unthinkable rimfire velocity of 2,500 fps, there seems to have been another discovery, another gleam of light in the dark recesses of the small-bore tunnel.

It’s a gleam of light, which even I, a confirmed devotee of big bores and heavy bullets, find most intriguing.

Once again, the team at Hornady who gave us the .17HMR have been leading cartridge development in association, this time, with Savage, the rifle builders.

Between them, they have managed, with the benefit of the latest research and technology, to produce a cartridge about which even the great P. O. Ackley could only dream.

NICE DIMENSIONS

There are certainly ‘wildcat’ .17s available and ‘Cartridges of the World’ describes the .17 Ackley Hornet as driving a 25-grain bullet at over 3,500 fps.

However, it couldn’t do that in Ackley’s time and Hornady and Savage are to be congratulated for taming the little wildcat.

If you do happen to own a rifle in .17 Ackley Hornet, the new .17 Hornet is NOT interchangeable with the Ackley version because of slight dimensional differences.

I’ve been promised a rifle for test as soon as one is available.

WHAT ABOUT THE BULLET?

Hornady have chosen to use their 20-grain V-Max bullet at a published muzzle velocity of 3,650 fps.

Trajectory, they say, is the same as that of a 55-grain bullet fired from a .223.

Hornady packs the ammo in 25-round boxes and says it’s significantly cheaper than the .223, working out about a $1 a pop in the US at the recommended retail price.

Reloading dies will certainly be available (strictly for those with nimble fingers, I reckon!) and I also expect that Hodgdon’s Lil’ Gun will be a good choice of powder.

As an aside, Lil’ Gun was developed for reloading smallbore shotguns, but 13 grains of it in my .22 Hornet drives a 35-grain V-Max at exactly 3,000 fps.

While the .17 Hornet will certainly kill foxes, it’s also likely to be used for crows, magpies and such so we need to look at zeroing to avoid shooting over the top of small targets.

If we say that the kill area of a magpie is two inches in diameter, we need to zero the rifle at a range, which keeps the bullet within one inch of the crosshairs throughout its travel.

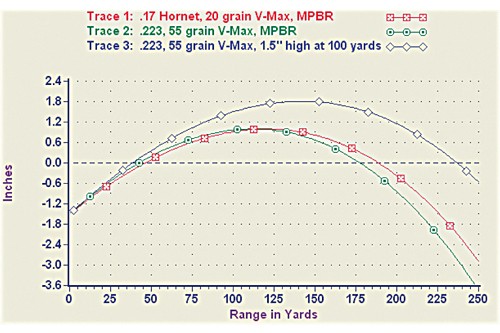

This is called the maximum Point Blank Range, or MPBR. The graph shows the .17 Hornet and .223 zeroed for a MPBR with a two-inch target zone.

As Hornady suggest, there is little difference in their trajectories and with either cartridge a good Shot could hold dead-on a magpie out to a little over 200 yards.

Even with a good ‘scope, they don’t look very big at that range!

The third trace, in blue, shows the 55-grain V-Max in the .223 when zeroed 1.5 inches high at 100 yards.

That’s fine for foxing but a close look at the trajectory shows that it would be very easy to shoot over the top of a magpie at ranges between about 80 and 210 yards.

The Savage M25 rifle will be available in three versions and, with Hornady ammo, will be imported by Edgar Brothers.

I can’t wait to get my hands on it!

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Shooting Times & Country

Discover the ultimate companion for field sports enthusiasts with Shooting Times & Country Magazine, the UK’s leading weekly publication that has been at the forefront of shooting culture since 1882. Subscribers gain access to expert tips, comprehensive gear reviews, seasonal advice and a vibrant community of like-minded shooters.

Save on shop price when you subscribe with weekly issues featuring in-depth articles on gundog training, exclusive member offers and access to the digital back issue library. A Shooting Times & Country subscription is more than a magazine, don’t just read about the countryside; immerse yourself in its most authoritative and engaging publication.