Iain Watson and Chris Rogers debate whether highland stalking or lowland stalking makes for finer sport

★ Win a Schöffel Country shooting coat for everyone in your syndicate worth up to £6,000! Enter here ★

Do we rely on scopes too much?

I once went out on the hill with an old stalker who bemoaned the use of bipods. This struck me as odd, because I would have thought using bipods meant fewer missed shots and, more importantly, fewer wounded beasts. But according to him, in using a bipod, his guests tended to raise their heads too high, risking detection.

He was rather set in his ways, that old stalker. He was also against sound moderators and I got the impression that he barely approved of telescope sights. In response to a question about his culling selection policy, he said: “If it stands sideways, it’s selected.”

A scope can alter the balance

I remembered him the other day, when I had to take the German scope off one of my rifles. The handling when the rifle was left with open sights only was a revelation. You forget how much a big scope can alter the balance and handiness of a rifle until you remove it. I suspect that most rifles used for hill stalking are over-scoped for the job.

Many of today’s scopes have huge object lenses, variable power, illuminated reticles and the like. A lot of them were designed for shooting from a high seat, with a need for optimum performance at dawn or dusk. It seems to me that they are not necessarily the right tool when you are out and about on the hill, or walking quietly through the woods, where a more compact, fixed-power scope fits the bill.

Hi-tech stalking

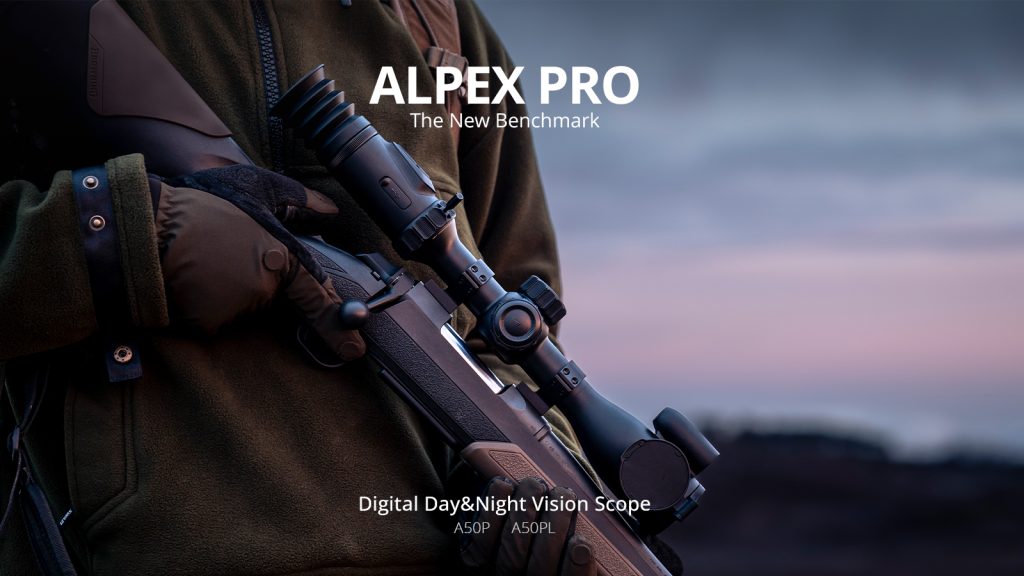

Is the latest hi-tech sighting system for stalkers ruining the sport element?

Non-shooters sometimes think a telescope sight confers an “unfair” advantage, imagining the idea is to shoot from a huge distance. In fact, the benefit of a telescope sight when stalking is the ability to place a shot more accurately at a reasonable range. For most of us, the distance at which the shot is best taken is probably not vastly more than it was in the days of open sights.

Fundamental skills of stalking

The skill in stalking lies in the use of fieldcraft to get within range of the deer so as to be reasonably sure of putting the bullet in the right place. The telescope sight and the bipod make shot placement more certain — which can only be a good thing. But the fundamental skills of stalking haven’t changed significantly since the days of the bow and arrow.

The professionals, when out on serious hind culling, sometimes take shots at ranges that are way beyond the ability of most of us. For me, a hind at 200m is a long shot. Beyond that, bullet drop becomes significant and difficult to judge, not to mention cross-winds.

Getting too close

Mind you, the old stalker I mentioned above believed there was such a thing as getting too close. He said that if he got his guest closer than 100m on the open hill, the deer were too likely to be spooked by a noise or a movement. He reckoned that 130m to 150m was the ideal distance. I tend to agree — though much depends on the terrain.

Curiously, despite carrying a rangefinder, I use it very rarely before taking a shot. Perhaps I would use it more if it was incorporated into my binoculars or sight. However, given the modest distances involved, I know full well when a deer is in range anyway.

Today, I hear talk about the use of various thermal-imaging devices. Instinctively, I don’t like the sound of this. And given the legal constraints on shooting deer at night, I cannot see the point — or am I getting a bit like that old stalker?

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Shooting Times & Country

Discover the ultimate companion for field sports enthusiasts with Shooting Times & Country Magazine, the UK’s leading weekly publication that has been at the forefront of shooting culture since 1882. Subscribers gain access to expert tips, comprehensive gear reviews, seasonal advice and a vibrant community of like-minded shooters.

Save on shop price when you subscribe with weekly issues featuring in-depth articles on gundog training, exclusive member offers and access to the digital back issue library. A Shooting Times & Country subscription is more than a magazine, don’t just read about the countryside; immerse yourself in its most authoritative and engaging publication.