Win CENS ProFlex DX5 earplugs worth £1,149 – enter here

How to curb nerves on your first working test

What can gundog handlers learn from sport psychology? Novice handler Emily Cartigny tries to curb the nerves in her first working test.

As I line my spaniel out for a blind retrieve, arm extended in front of me, I can feel the nerves rattle through my body. My hands feel twitchy, my stomach is fluttering, and my mind is racing with mostly unhelpful thoughts. In three weeks, I would be taking part in my first charity working test and I knew this level of nerves was not good. The test was hosted at my local training group, Claudia’s Canine Coaching, which added an extra layer of rivalry, desire to do well, and yearning to show off the hard work we’ve put in. In my head, full of naivety that comes with training your first dog, my two-year-old sprocker, Merlot, is the perfect model. To think my bubble of positivity might be popped with a hearty dose of reality was anxiety-inducing. While I’m new to the world of gundogs, I’ve spent most of my life playing, competing, and working within sport. When faced with a new form of competition, I wondered if some basic sport psychology techniques could give my dog the best opportunity to succeed and help me curb the rising tide of nerves? After returning home, I got straight to work.

Managing expectations

First things first, I needed to manage my expectations. So, without thinking, I wrote down my current ambitions: 1) get 20 points (the maximum) on each test and 2) win the spaniel category. I quickly realised I was setting myself up to fail on two fronts. The first: I was focused on outcomes I had no control over. In the sporting world, the phrase ‘control the controllables’ gets used frequently. I have no control over the score the judge is going to give me or how well other competitors do. Even if we performed the tests perfectly in my eyes, we still might not score 20s or win the spaniel category. Secondly, I was setting my expectations far too high. As a highly competitive person (the kind you probably don’t want to play a board game with), I sometimes need to reign the ambition in. At our first test, expecting perfection was unrealistic.

Instead of letting these unhelpful expectations run away with my nerves, I decided to reframe them. I tried again to write down my expectations. The second time I wrote:

1) enjoy the day, 2) Merlot attempts all tests, 3) she copes well with shot and 4) calm and (mostly) capable handling from me. Sitting back and looking at my new expectations, my nerves dissipated. All of these things I could control and were all within our capabilities.

Preparation is key

The next step was feeling prepared. Part of this was training and working on our weak areas, but the other part was actually understanding what we’d let ourselves in for. I started asking questions of anyone and everyone, and before long the phrase ‘J Regs’ came up. “What even are they?” I thought to myself as I opened up the

50-page document from the Kennel Club which outlines all the rules and regulations for working tests and field trial competitions. Did I read all 50 pages cover to cover? No, I can’t say I did. But the page that covers the eliminating and major faults was useful to help me understand what behaviours would be expected of my dog and hopefully what to avoid.

Where it started to go wrong

The day of the test finally arrived. The cars crunched their way up a gravel path to be greeted by friendly faces. A whole range of dogs and handlers turned out, from those who were there to give it a go, expecting nothing, to those who were well-versed in working tests. We caught up with friends and headed over to warm the dogs up on a dummy launcher. This is where it all started to go wrong. For several reasons, one likely being my nerves, Merlot was not her usual self. She went out for the warm-up dummy but kept coming up too short and no amount of my stop whistle and pushing her back was helping. I could feel the eyes of my peers on my back, and the sweat started to bead on my forehead, despite it being a typically cool English summer’s day. In the end, I stopped her, picked up the dummy myself and put her back on the lead. This was not the start I had planned.

The run of bad luck continued on to the first test. It was so flawed I’ve mostly wiped it from my memory. I only remember a comment from my partner, Tom (who had volunteered to dummy throw): “I’ve never seen Merlot not deliver a dummy before!” I tried convincing him and myself: “It’s fine,” when in reality I was completely disheartened. I went back to my car, sat on the open boot and put on my baseball cap, thinking I could hide behind it for a while. I also dug out my notebook and opened it to the page where I’d written down my expectations. The first one jumped out at me: Enjoy the day! Convinced we had two zeros for the first test, I let the pressure completely release and planned to use the rest of the tests as a training day instead.

Performance routine

The idea behind installing a routine into competitions is one used by many (if not all) elite athletes. Next time you watch someone take a penalty or a conversion, you’ll be sure to spot some. This is a series of systematic behaviours and thoughts the person goes through before every performance, with the aim of putting them in a confident and focused state of mind. Michael Jordan, one of the greatest basketball players of all time, would spin the ball in his hands, bounce it three times, and spin the ball once again before taking a free throw.

I’ve previously worked with a trainer, David Holmes, who always insisted on putting your lead in your pocket before every exercise and then back on at the end. At first, I thought he was just being fastidious. But now I see the importance of this behaviour and it made up the main part of my performance routine. I took my spot, brought the dog to heel, took her off the lead, put the lead in my pocket, breathed, relaxed my shoulders, put my whistle

in my mouth, watched the mark, breathed, waited for the judge’s go ahead, lined her out, sent, breathed, handled (if needed), waited for the delivery, brought the dog back to heel and then gave the dummy to the judge. From here, I could go back through the process for the second part of the test: breathe, relax my shoulders, put my whistle in my mouth… etc.

In reality, especially on the first test, I don’t think I took a breath until the dummy was back in my hand. I lined out before the judge told me I could go (who kindly and quickly said “you can send when you’re ready”), and I pocketed the dummy instead of giving it back. But the basic framework was being built. Particularly the breaths in between, when I remembered them, helped me to control my emotions mid-test. It stopped me from jumping on the whistle too early and instead allowed me time to trust her to work. Focusing on the process also stopped me from analysing, overthinking and dwelling on any negatives. The time for reflecting can come later, but at that moment the priority was to get the job done. With my performance routine, and now enjoying chatting to like-minded people (mostly about dogs), both Merlotand I started to loosen up. At times, I almost forgot we were competing. We finished on test four with some of the best work I’ve ever seen her do.

My fried egg theory

After the dust had settled on the day, I took to pen and paper once again to take stock and reflect. My intention was to write three positive points and three areas to work on. Instead, I couldn’t limit myself to just three and wrote down 10 positives. I was incredibly pleased (and surprised) at how well the small techniques I’d used had helped me manage nerves, cope in difficult situations, and get the best out of my dog when I could have easily packed up and gone home after test one.

I mainly wanted to understand why Merlot’s delivery, something she’s usually so good at, had unravelled in that first test. As I sat contemplating, looking at my fried egg sandwich (if you’ve not tried it, it’s the best), I couldn’t help but see the comparisons. When you put the pressure on, some of the good stuff is bound to fall out the sides. Instead of being completely demoralised, it was actually to be expected (at least until we both become more comfortable in that environment) and is now something I’ll be ready for in the future.

A success for everyone

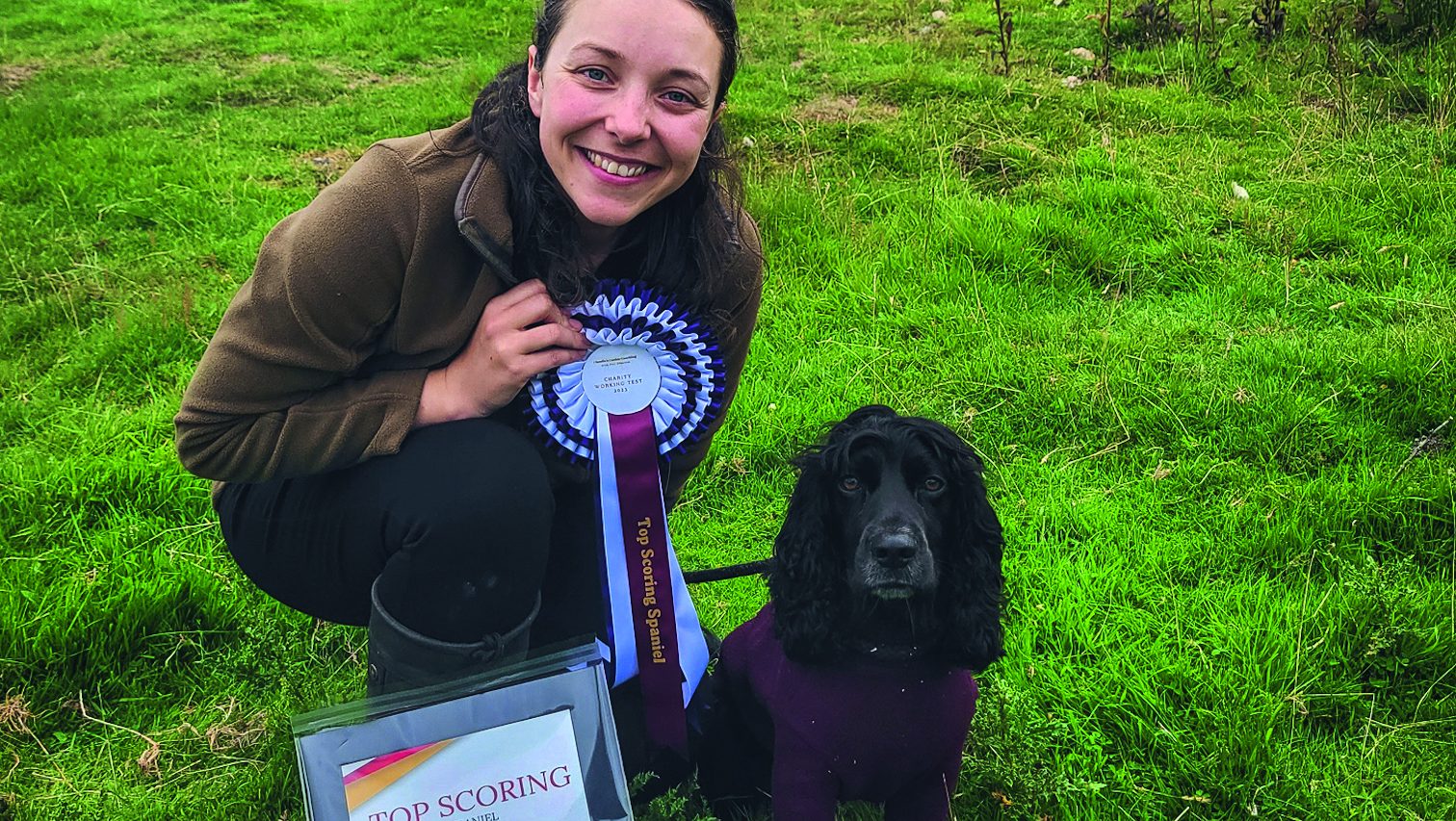

I almost don’t want to share the actual result from the day, because in the end the scores genuinely didn’t matter. We achieved all our expectations, we had fun with some of the best people, and we came away with a new motivation for training. In the same breath, it’s also exciting to share with you: we won! Merlot was the highest-scoring spaniel on the day. We hadn’t done as badly as we thought on test 1 and even came away with some 20s on the later tests. While this really shows the benefits of thinking about your own mindset, coping strategies, and reflections, the real winner was the day itself and a complete reflection on those who organised it.

The entire day had a welcoming and supportive atmosphere allowing friends to catch up, laugh through their mistakes, and learn with their dogs whilst remarking: “well, it’s cheaper than a training day!”. It also offered an opportunity to test our dogs which many of us don’t have access to. In fact, all the winners (highest scoring: Overall, Retriever, Spaniel, and Minority dog breed) were non-KC-registered dogs. This success is a testament to all the communities in this world that allow any dog and their handlers to access the benefits of gundog training. To top it off, over £1,000 was raised for North West Air Ambulance. A huge success on all accounts.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Shooting Times & Country

Discover the ultimate companion for field sports enthusiasts with Shooting Times & Country Magazine, the UK’s leading weekly publication that has been at the forefront of shooting culture since 1882. Subscribers gain access to expert tips, comprehensive gear reviews, seasonal advice and a vibrant community of like-minded shooters.

Save on shop price when you subscribe with weekly issues featuring in-depth articles on gundog training, exclusive member offers and access to the digital back issue library. A Shooting Times & Country subscription is more than a magazine, don’t just read about the countryside; immerse yourself in its most authoritative and engaging publication.