News

The myth of the “easy” bird

Talk of "easy" and "hard" birds is a fiction, says Blue Zulu, as quarry and conditions have their own ideas

Would you like to speak to our readers? We offer sponsored articles and advertising to put you in front of our audience. Find out more.

“For my money, the hardest shot of all is the snipe,” opined one of my close shooting chums as he chomped on an elevenses sausage roll. Cue nodding heads and crumb-sprayed agreement. I kept shtum, because the shooting gods are tricky buggers and you don’t want them dropping your sliced toast of good fortune buttered side down on to the ordure.

Yet the last time I shot driven snipe they were, well, easy. Three of them came off a piece of damp moorland in Co. Durham, hung in the wind and I dropped them with three single consecutive shots. My Irish mates, who see plenty of snipe meet their maker, were full of hand-pumping congratulations, but actually the birds may have seemed stratospheric, but were in reality no more than 35 yards up. And every one of them had followed the same line, so since I’d found the first, the others followed its downward spiral into the ghyll below.

On the other hand, some birds with an “easy” reputation can be downright hard. Take decoyed pigeon, for example. Toddle off for a day with a professional pigeon guide and he’ll be narked if you don’t clobber a pidge with three cartridges or fewer, which is reasonable if there are loads of birds coming straight into the middle of the decoy pattern. But if they have learned that the whirler is actually a carousel of doom, and flare at the edge of the pattern, then those same pigeon would defeat Ripon at his ripping best.

Grouse are no different. My experienced grousing chums advise, quite rightly, “to go for the easy ones,” by which they mean always select the two that look most vulnerable when that covey comes swirling round your ears. Early in the season, especially when the birds are young and on a plentiful moor, such decisions are easily made and the old hands can easily pop off one for every two shots.

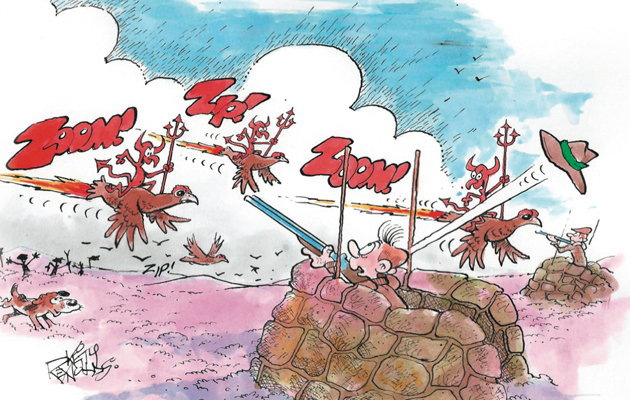

But come October it’s a different story. The grouse are bigger, wilder and packed up. Add a good dollop of Yorkshire wind and rain and those “easy grouse” are now storming over the line with the devil up their tails. Even if they are coming straight over, you will struggle to drop them and the problem worsens when you’re at the fringes of the action.

All too often, you will see a pack careering along your sight horizon, following a parallel path to the butts and only just in range. Then you can either take a full cartridge bag up and down the hill and preserve your reputation as being a “tidy Shot” or you can stop worrying about your cartridge-to-kill ratio and lay down the lead. You will miss more than is comfortable, but those long-crossing grouse, when you connect, will be the ones you recall on the drive home

Shoot with conviction

Somewhat perversely, the “easiest” birds are often the hardest. For me, the toughest shot of all is the “shall I, shan’t I” bird, especially a pheasant. How many times have you seen a cock bird emerge from the coverts and start climbing steadily towards you, 20 yards up? You shuffle your feet, line up the muzzles and wait for it to climb another 10 yards higher before you take the shot. Except it doesn’t. It keeps at that infuriating hedge-clearing 20 yards. It wouldn’t matter if it were a partridge, when you could reasonably be expected to take it well in front. You would then commit fully, it being a decent sporting shot, and down it would come. But we’re not really expected to shoot pheasants like partridges, so we wait for the brute to come overhead and hopefully gain altitude. It doesn’t, so what next?

At a shoot blessed with gallons of good birds, it’s not a problem: we simply raise our hats and let it sail on. There are hundreds of shoots, however, where the pheasants suffer from vertigo and are never going to rise higher than 20 yards. So you can either keep your gun lowered or try to deal with enough of them so that your host is not offended.

In theory, these big-bomber birds, lumbering over the line, should be the easiest shot in the world and so they are, on boys’ shoots, where enthusiasm is rampant and most of the line is armed with 20s and .410s. But for experienced Shots the moment that horrid “shall I, shan’t I” creeps into the brain the bird is as good as missed, to the unrestrained joy of the neighbouring Guns.

Miss an absolute “sitter” and you can be sure that’s the bird that’s the talk of the Gun bus, not that rather splendid steeple-clearer you shot three minutes earlier. And if you do hit it with a hefty load of 5s the only reward is the cloud of shame of drifting feathers pointing directly at you. The only time I don’t make a hash of these ridiculously “easy” pheasants is when the gloves come off for the cocks at the end of the season. Then you shoot with real conviction and down they come, as easy as pub skittles.

Three weeks ago I made a pretty good job at some grouse flipping along the horizon 45 yards in front of my butt. They were “difficult” in theory but demanded total concentration and so dropped in sufficient numbers to earn a kind word from the underkeeper doing the flanking. Yet as he was speaking I was recalling a windless, hot day the previous September when I missed “easy” partridge after “easy” partridge and could sense my host scratching me from this year’s invitation list. All of which proves the wisdom of Eddie the farm worker when he took me roughshooting some 40 years ago. “Do you know what’s the hardest shot in the book?” he asked, as I missed a cock pheasant rising up some 15 yards in front of me, “It’s the one you’ve just missed.”

Related articles

News

PETA attacks royal couple for breeding cocker pups

The Prince and Princess of Wales have faced criticism from animal rights group PETA after they had a litter of puppies

By Time Well Spent

News

Farmers launch legal review against Reeves’s farm tax

Chancellor Rachel Reeves faces a judicial review over inheritance tax reforms that could force family farms out of business

By Time Well Spent

Manage Consent

To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us to process data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

Functional Always active

The technical storage or access is strictly necessary for the legitimate purpose of enabling the use of a specific service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user, or for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of a communication over an electronic communications network.

Preferences

The technical storage or access is necessary for the legitimate purpose of storing preferences that are not requested by the subscriber or user.

Statistics

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for statistical purposes.

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for anonymous statistical purposes. Without a subpoena, voluntary compliance on the part of your Internet Service Provider, or additional records from a third party, information stored or retrieved for this purpose alone cannot usually be used to identify you.

Marketing

The technical storage or access is required to create user profiles to send advertising, or to track the user on a website or across several websites for similar marketing purposes.