News

Hunting methods you don’t hear of

Would you like to speak to our readers? We offer sponsored articles and advertising to put you in front of our audience. Find out more.

There was a time when the only way it was possible to engage in exotic game hunting in untamed and dangerous corners of the globe was to be called something like Baron Bror ‘Bullet’ von Blixen-Finecke or Lady Grizel ‘Killer’ Cochrane. These professional hunters and adventurers had been sired from long lines of bloodthirsty aristocrats and were often the inspiration for morally dubious fictional characters like Rider Haggard’s Allan Quatermain.

To even locate an account of such hunting required lighting a paraffin lamp and exploring the forbidden section of some country library, blowing the dust from a hessian tome and diving in. Things are somewhat different now; no longer is game hunting limited to those of high birth and conservation is a huge part of why it is allowed to continue.

Shooting an ostrich in Africa can be done for as little as £500, and if you are interested in such things a quick bit of searching online will throw up all sorts of options as well as showing you the best prices for cape buffalo hunting. Gone are the days of the boomerang and the bolas, yet it is still possible to ethically skewer a boar in Spain or catch a capercaillie unawares with a rifle in Scandinavia.

In recent weeks I’ve been exploring some of the world’s more exotic modes of hunting. Many of them are ancient and quite a few I’d never even heard of before.

Pigsticking, Spain

Modern Iberian pigsticking generally takes the form of an individual or a group of talented riders on highly trained horses, pursuing a wild boar with specialised spears. The spears have a hilt of sorts that prevents the pierced boar from making its way towards its assailant down the shaft. In Spain, this seemingly archaic sport is alive and well after having been formally legalised in 2012. It is legal in a number of autonomous regions such as Andalusia and Castilla-La Mancha, where the sport is largely conducted through the sparse and gently grazed oak forest. There are numerous hunts that engage in the sport on private land, with the most prominent one being the Club de Lanceo Español.

Since the sport’s renaissance, it has become highly ritualised, with prayers often said before the hunt commences. Hunters can chase a single boar all day and often the animal gets away. If they are successful, they feast on what they kill or send the meat to Germany, Europe’s greatest consumer of wild boar.

Lord Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the boy scout movement, spoke passionately of his time in late-Victorian colonial India spent pigsticking. “Try it before you judge. See how the horse enjoys it, see how the boar himself, mad with rage, rushes wholeheartedly into the scrap, see how you, with your temper roused, enjoy the opportunity of wreaking it to the full. Yes, hog hunting is a brutal sport – and yet I loved it.”

The wild pig has long been a quarry of note – boar hunting appears in Homer’s rendition of the hunt for the Calydonian boar and the earliest artistic depiction of any animal is a warty pig in an Indonesian cave believed to be over 45,000 years old.

Hunting with raptors is an historic sport in the Arabian Peninsula, where the bustard was once a favoured quarry

Bustard hunting, Arabian Peninsula

Hunting with raptors is a tradition as old as the dunes over which it takes place, but its modern form has become increasingly controversial as the nature of the practice has altered in line with societal shifts in the Middle East. Historically, nomads would head out into the desert with saker falcons (large falcons that in a dive are only bested in speed by the peregrine and the golden eagle).

The elegant, long-legged houbara bustard, sized somewhere between a chicken and a turkey, has traditionally been the favoured prey species for Arabian falconers, in part due to its meat’s fabled properties as an effective aphrodisiac.

Sadly, across the Arabian Peninsula the bustard has effectively been wiped out in the wild, and now the hunters and their falcons are pursuing the thinning population across central Asia. The most pressing problem is the scale of the modern hunts. Outings used to be small affairs, with one or two birds and a few tents, yet now convoys of Land Cruisers charge across deserts and steppes, accessing areas that would once have been too remote or challenging to reach, and releasing multiple falcons into the air.

As a result, huge numbers of prey animals can be slaughtered during each hunt. In 2014, an official report was leaked revealing that a Saudi prince had killed over 2,000 birds in a single three-week hunting expedition in Pakistan. In 2015, a Qatari prince was fined and two of his extremely valuable hunting falcons (worth £200,000 each) were seized when he was caught pursuing houbara bustards in north-western Pakistan without a permit, but this enforcement of the law was an exceptional case.

The value of trained falcons has become highly inflated because of the wealth of the hunters, encouraging more people to trap and train birds, and fewer falcons are being released into the wild at the end of the hunting season (as they were traditionally).

Capercaillie in Scandinavia

Capercaillie hunting, Scandinavia

The capercaillie, or western capercaillie, is found in differing densities across northern Europe and Asia. In Britain, they became extinct in the mid-18th century and were then reintroduced in the mid-19th century from Swedish populations. Their numbers in Britain have plummeted from around 20,000 in the early 1970s to just 1,000 today, leaving them extremely vulnerable.

In Scandinavia and some of the Baltic states however, their population has remained steady enough for some hunting to be allowed. European populations sit at around two million birds.

These turkey-sized, almost flightless members of the grouse family are hunted in two main fashions. In the winter, when you are only allowed to hunt the roosters, in the stunted forests of the Scandinavian north it is common to set off on capercaillie stalks on crosscountry skis with rifles. Decked out in snow camouflage, hunters creep up on their quarry. It is said that for the last few seconds of their calling displays, the male birds are unable to hear, so the hunters use this moment to inch closer to these blueberrymunching avians.

Outside of the winter season, from August to November, hunting usually takes place with pointers or traditionally Finnish spitz dogs, which flush the birds out to be shot or keep them pinned until the Guns arrive.

Hunters in Scandinavia take very low numbers of birds each year, yet the tourism they promote contributes to conservation significantly in the areas that this majestic, gurgling bird thrives. It is said that due to the capercaillie’s winter diet of almost exclusively pine needles, that its flesh smells and tastes like resin, making them deeply unpalatable for humans.

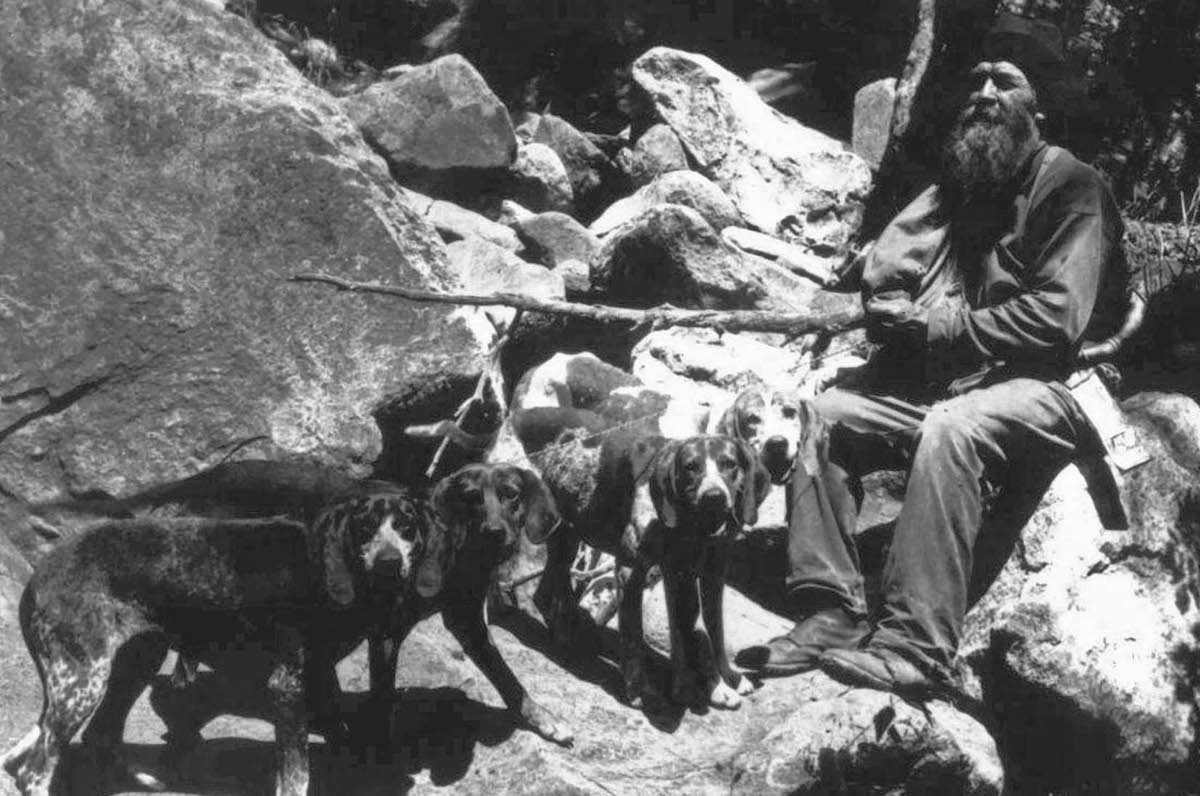

Benjamin Lily was a famed bobcat hunter in early 1890s Midwest America, using hounds to track the diminutive member of the lynx family

Bobcat hunting with hounds, North America

Bobcats are the smallest member of the lynx family and can be found in almost every corner of continental North America, from Arizona to British Columbia. They thrive in areas from boreal forests to semi-desert and are far more common than a number of their relatives. Whereas the Iberian lynx had fallen to a population as low as 300 in the early 21st century, current estimates of American bobcats are around three million, and thus with the appropriate licence they can be legally hunted.

The traditional method is to do so with hounds. Bluetick coonhounds, black and tans or leopard curs remain popular choices, and were often used by the famed Midwest hunter Benjamin Lilly in the early 1900s. Modern hunters in mountainous states like Idaho will wait unit there is snow on the ground, as this makes these approximately spaniel-sized cats easier to track.

There are an estimated three million bobcats in the US, where they can still be hunted with hounds

Bobcats prefer to kill their own food, rarely stooping to scavenging, and thus baiting leads to meagre success. Hunters most often pursue their hounds and the bobcat on foot but can do so in trucks or on horses, depending on the terrain and the distances. Hunts can often be far-ranging, as a male bobcat territory can be up to 25 square miles.

Once the hounds are on the scent, they aim to ‘tree’ the bobcats as these creatures are equally as at home in the canopy as they are on the ground. Once they have rushed up a tree, a carefully aimed shot will bring the animal down.

In the Rocky Mountains, the less sustainable practice of hunting cougars in the same fashion is still undertaken. These can weigh up to 100kg, but their population sits at only 30,000 across the US.

Hunters must get close enough to an ostrich to successfully kill the speedy bird with an arrow

Bowhunting ostrich, South Africa

It is currently a booming business to take on one of Africa’s fastest animals, the ostrich, with one of the oldest weapons still in use, the bow and arrow, although today’s carbon fibre compound bows are not quite what Henry V would have seen at Agincourt. Modern bows are designed to kill large animals chiefly through blood loss and catastrophic tissue damage resulting from their broad-bladed arrow-heads with the gruesomely named ‘bleeder’ attachments.

Due to the relatively low speed of an arrow when compared to a bullet, it increases the necessity of a skilled stalk and a close shot. Ostriches can be stalked across large swathes of Africa and in South Africa they can be legally hunted from the fringes of the Kalahari Desert to the Limpopo.

To offer a good chance of a quick kill, it is essential that the hunter fires the arrow from no more than 25 yards away. The legal requirement is that the arrow achieves a speed of at least 245fps, as the projectile must get through a layer of feathers and still have enough kinetic energy to bring down an animal that can weigh up to 140kg. If you are not careful and spook the world’s largest bird, they can tear off at up to 70km/h.

It is also imperative that you make sure that your quarry is fully incapacitated, as the kick of an ostrich has been known to disembowel wild dogs and could easily kill a man. As a trophy, these giant, flightless birds have little value, but they are renowned for being delicious and extremely low in cholesterol.

Related articles

News

Anti-grouse shooting petition crushed by MPs who don't even shoot

Wild Justice's petition to ban driven grouse shooting was quashed in Westminster Hall yesterday, with all but one MP opposing the ban

By Time Well Spent

News

A sound decision as moderators to be taken off licences

The Government has finally confirmed what the shooting community has long argued – that sound moderators should be removed from firearms licensing controls

By Time Well Spent

Manage Consent

To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us to process data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

Functional Always active

The technical storage or access is strictly necessary for the legitimate purpose of enabling the use of a specific service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user, or for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of a communication over an electronic communications network.

Preferences

The technical storage or access is necessary for the legitimate purpose of storing preferences that are not requested by the subscriber or user.

Statistics

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for statistical purposes.

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for anonymous statistical purposes. Without a subpoena, voluntary compliance on the part of your Internet Service Provider, or additional records from a third party, information stored or retrieved for this purpose alone cannot usually be used to identify you.

Marketing

The technical storage or access is required to create user profiles to send advertising, or to track the user on a website or across several websites for similar marketing purposes.