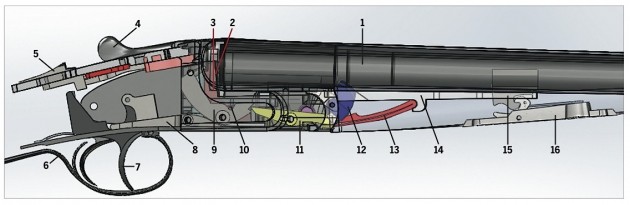

Do you know your hammer from your extractor? Here is a clear explanation of the functions of named parts of…

Gear

A short history of the shotgun

Would you like to speak to our readers? We offer sponsored articles and advertising to put you in front of our audience. Find out more.

A very long time ago, some enterprising person decided to fill a tube with gunpowder, put a rock or something equally solid on top, light the blue touch paper and stand back to see what would happen.

At this point the firearm began its evolution, though the shotguns we use today have come a long way since. What, though, were the really important points along this path? Here are my suggestions for the top five.

Black powder (left) is far dirtier than modern, smokeless powder (right)

1. Gunpowder

Let’s face it, gunpowder was the logical beginning. The very first written reference to a powder made from three substances (presumably charcoal, saltpetre and sulphur, the basic ingredients of gunpowder) that would “fly and dance” was by a Chinese alchemist in AD142, and the first actual gunpowder recipe certainly comes from that country.

Originally seen as an amusing diversion, people soon caught on to its potential as a weapon of war and fire arrows, “thunderclap bombs” and the “fire lance” appeared on the battlefield. The latter was usually no more than a bamboo pole with a slow match, used to jet flame at a close quarters enemy. It was from the fire lance that the first gun, a simple metal or bamboo tube at the end of the lance, evolved.

2. The trigger

The humble trigger is often overlooked but until a remote way of setting off a charge of gunpowder was developed, it was impossible to truly aim a firearm. Having to manually align a slow-burning fuse with a touch hole or a pan of priming powder does not really encourage accuracy.

Early triggers were simple things, little more than basic levers that moved the smouldering fuse into the right position, but more elaborate spring-loaded affairs soon developed. These in themselves allowed the firing mechanism to produce sufficient force to create sparks from flint and iron, as in the flintlock, and later of course a firing pin that would strike a primer hard enough to detonate the explosive compound inside.

The flintlock was in common use until it was replaced by the percussion cap

3. The percussion cap

This development, as far as I am concerned, was The Big One. Up until the early 1800s, flint and steel were still the state-of-the-art firing mechanism. That was until the discovery of fulminate of mercury, a highly volatile substance which only needed a sharp blow to detonate it.

A Scottish clergyman, the Reverend Alexander James Forsyth, used fulminate of mercury to replace the flint of the gun, and also replaced an unreliable external pan of priming powder with a straightforward hammer which ignited “detonating powder” directly into a vent which led to the main powder charge. This revolutionary system was patented in 1807 and the percussion principle was born.

Things then moved quickly, and Forsyth’s detonating powder was improved upon by other inventors. One early system involved pills of powder, coated in varnish and placed into the vent, to be struck by the hammer. Another sealed small pinches of detonator between two pieces of paper, much as the modern day caps used in children’s toy guns are today. However ultimately, the powder was put into a short copper tube with a closed end; the open end was placed directly into the vent and crushed by the falling of the hammer to fire the powder.

The final logical progression was a small copper “hat” with a small coating of detonating powder inside it, which was placed onto a nipple over the vent and fired by a hammer in much the same way. Who was actually first to invent this, the percussion cap, is much disputed and several people claimed the credit.

Whatever the case, the percussion cap was firmly established by the early 1820s. Without it, firearms development could never have progressed as it did, and the breechloading gun with an all-in-one cartridge would not exist as we know it.

Shotgun mechanisms developed rapidly throughout the 1800s.

Little has changed in shotgun innovation since successful hammerless guns were developed in the 1870s

Breechloading

As long as sportsmen were confined to muzzle-loading shotguns, gameshooting was usually conducted “walked up” over pointing or setting dogs. Once a shot had been taken, a party would have to halt to allow the firer to reload. It was not until the advent of rapidly-reloaded breechloaders that driven shooting as we know it became truly practicable.

We can thank a Frenchman called Lefaucheux, who presented an innovative new design at the 1851 Great Exhibition. His revolutionary firearm was no muzzle-loader but instead featured hinged barrels, allowing the introduction of complete cartridges containing shot, powder and a fulminate mixture to ignite it, all in one package. A pin protruded from the cartridge and out of the breech end of the gun, where it could be struck by an external hammer and fired. Surprisingly, it didn’t catch on immediately; the gun was criticised for its weight and heavier recoil compared to the muzzle-loaders in use at the time. However, the pinfire cartridge was born and provided a building block for what quickly became a new fashion for breechloaders.

The main problem with the pinfire was the fragility of the pins protruding from the cartridges themselves. The first centrefire cartridges appeared in 1861, introduced to Britain by Mr George H Daw. In these, the percussion cap that had previously sat on a nipple on the exterior of a muzzle loader was relocated and sunk into to the base of the cartridge itself, where it could be struck by a firing pin contained within the internal mechanism of the gun.

It was safer, less fragile and quicker to load than the pinfire, and the 1860s shooter would find little difference between his early firearm and a more recent hammer gun. By 1871, the first really successful hammerless gun had been developed and, barring a few simple innovations, the shotgun has evolved very little since then.

The parts of a shotgun cartridge explained

The different parts of a shotgun cartridge explained

A handy A-Z guide to shooting terms

An A-Z guide to shooting terminology with the jargon and vocabulary you’re likely to come across

Smokeless powder

Gunpowder is very basic stuff. It’s slow burning, unreliable, dirty and leaves about half of its mass behind in the form of corrosive residues. Furthermore, black powder produces smoke, which obscures the shooting field and takes time to disperse. You couldn’t see much when a number of guns were discharged at the same time.

Cleaner and more efficient propellants started to appear from the 1840s onwards with the appearance of nitrocellulose and nitroglycerine. The result has been increased visibility, essential especially for driven shooting, as well as less corrosion damage to the guns themselves. Those of us who are less than fastidious about gun cleaning would find their guns not surviving very long if left to be attacked by black powder residue.

There have certainly been many more developments; riflemen will no doubt cite rifled barrels, optical sights and moderators, pigeon shooters may favour automatic reloading systems and wildfowlers might want to include choke but, for me, these are the top five innovations.

Without them, we would not have the modern shotgun we use today.

Related articles

Gear

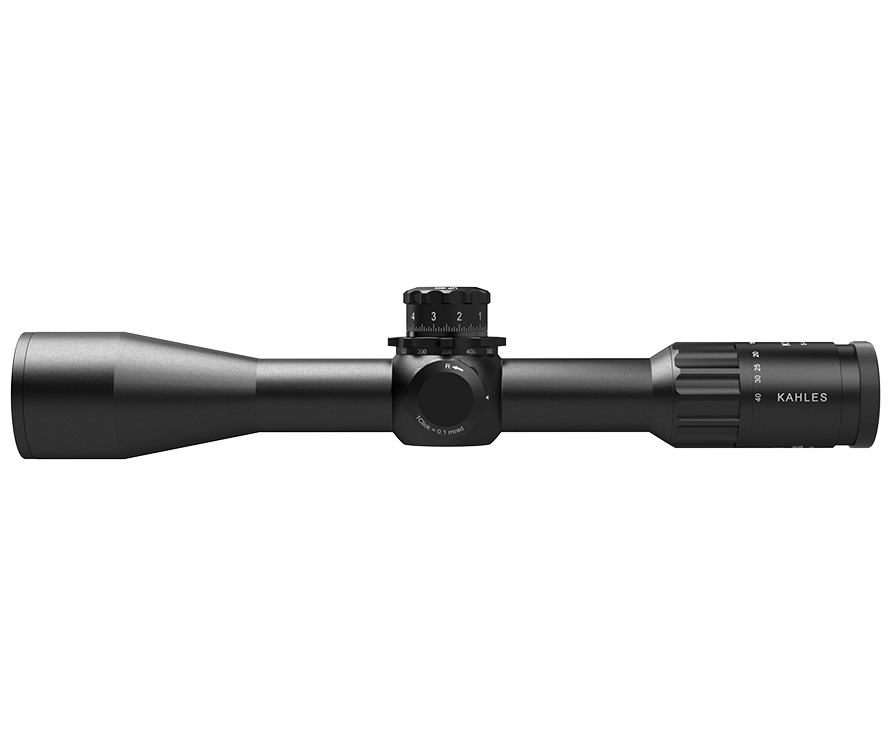

KAHLES K540i THE GAME-CHANGER – 40X

KAHLES introduces the revolutionary K5-40x56i—a new era in long-range shooting optics. With a 40% wider field of view, an exceptionally comfortable eyebox, and precision performance even at 40X magn...

By Time Well Spent

Gear buying guides

It’s an extra set of eyes, day and night

A trail cam is an invaluable tool for learning what’s on your patch and, even more importantly, what it’s doing, as Will Pocklington discovers

By Time Well Spent

Manage Consent

To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us to process data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

Functional Always active

The technical storage or access is strictly necessary for the legitimate purpose of enabling the use of a specific service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user, or for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of a communication over an electronic communications network.

Preferences

The technical storage or access is necessary for the legitimate purpose of storing preferences that are not requested by the subscriber or user.

Statistics

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for statistical purposes.

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for anonymous statistical purposes. Without a subpoena, voluntary compliance on the part of your Internet Service Provider, or additional records from a third party, information stored or retrieved for this purpose alone cannot usually be used to identify you.

Marketing

The technical storage or access is required to create user profiles to send advertising, or to track the user on a website or across several websites for similar marketing purposes.