The countdown is on for The British Shooting Show – book tickets online today and save on gate price!

How can we breed the perfect Labrador?

Labrador retreiving pheasant

Usd 29 nov 17 cover

Labrador retreiving pheasant

Usd 29 nov 17 cover

The Labrador retriever was first recognised by the Kennel Club as a breed in 1903. It was originally known as the St John’s dog or lesser Newfoundland dog. The breed was in Newfoundland in the 1700s and imported to England in the 1800s.

When I was researching its origins, I came across the same old photograph over and over. There are clear similarities between my own Swiftlands Briar and one of the original St John’s dogs in the photograph that I found.

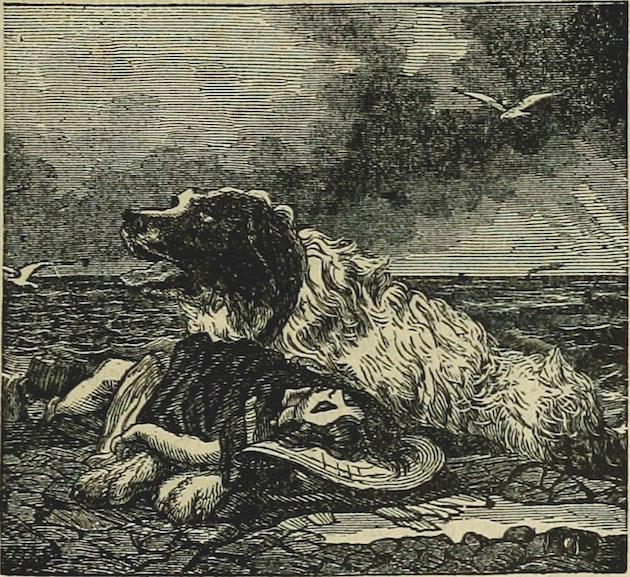

Nell, one of the original St John’s dogs, in 1867, when she was aged about 12

The dog in the image is Nell, pictured in 1867. She belonged to the Earl of Home and is an example of the type of early St John’s dogs that were imported to England from Newfoundland. Though Nell has white toes, you can still very much see the origins of the modern Labrador in her face, the set of her ears and in her neat body and short coat.

In addition to white markings on feet and often on the face too, St John’s dogs typically had a white chest patch that we still see in Labradors today. The patch is listed in the Kennel Club’s breed standard, as is a small fleck of white on the pasterns of the feet. This trait can be traced back to Banchory Bolo, the first dog to earn a dual championship, winning the bench title as well as becoming a field trial champion in England. Many dogs today can be seen carrying this trait and it is referred to as ‘Bolo pads’.

Though white markings tend not to be favoured by show dog enthusiasts, they are tolerated in the working community, especially in yellow Labs where they are not so obvious.

Ellena with her Labradors

Dual purpose

Looking back at these early photographs and paintings, it is clear to see that originally more breeders and trainers were motivated towards producing dual-purpose dogs. It is pretty difficult today to find a successful trialling dog that would hold its own in the show ring and vice versa.

Breeding a good line of Labradors takes time, commitment and money, with many hurdles to overcome on both sides, so it is not surprising that most breeders dedicate their lines to one discipline or the other.

Over time, the breed has separated more and you could be forgiven for mistaking the two types of Labradors as different breeds. The show type has become heavier and shorter-legged, with larger heads, as the breed standards were taken to the extreme. The working/trialling Labrador has become somewhat finer, leaner and faster in a bid to produce a more athletic and agile dog.

It is easy for either side to stand back and criticise. The working world often comments on the show dog’s inability to chase down a wounded bird running full tilt in thick cover or to maintain the stamina needed for a full day’s work. The showing world, in response, often looks at the working Labrador as totally unrecognisable from its origins and not to breed standard, referring to them as more lurcher types.

As with anything, beauty tends to be in the eye of the beholder. I have written before about the working ability in relation to colours of Labradors, which is another topic hotly debated, with examples of good and bad in all colours. The logical conclusion is that a good dog cannot be a bad colour. For me, this rings true for the looks and types of Labradors.

Those who have met me and my dogs will know that one of mine, in particular, has little resemblance to the traditional heavyset and larger-headed show dog. Her ears stick out, rather than folding neatly and being set correctly on her head. She is smaller, slighter and much quicker than most Labradors. Her ancestors were not like her in their physical attributes.

When I decided to compete, I was met with some hostile opinions due to her unpopular looks. However, as competition dogs go, I couldn’t have asked for more. She has proven herself time and time again in the shooting field, showing fearlessness in cover, the heart of a lion retrieving everything from Canada geese to squirrels and all in between. She has been placed and won Guns’ choice at open standard trials, along with numerous wins in all-aged and novice trials, and is consistently placed in working tests.

She is not alone with her odd looks. More and more of these smaller types can be seen working. While I am incredibly proud of her and wouldn’t change her for the world, it is vital that as a community we attempt to hold the breed together. The more we criticise and shun the other side, the more the breed separates.

The breed standard was originally created for a reason, to ensure the Labrador was fit for purpose.

However, some dogs being bred for extremes of these physical characteristics have lost the ability to be fit for the job they were meant for. The same has happened with other breeds, such as the German shepherd. Those in the show ring are never used, or even fit for use, as they were originally designed. However, other hunting breeds, such as the German shorthaired pointer, have managed to maintain an animal that is fully functioning, fit for purpose and successful in the show ring.

Breeders appear to have moved away from the goal of producing a dual-purpose dog

Breed traits

So how does the Labrador find its way back? As a breeder, I prioritise traits that I am looking for. I breed for temperament, health and working ability. If any of those is even in the slightest doubt, I will not consider using them.

I also think about what is missing. The only thing my line currently lacks is bone and a more typical head. This has been a consideration in each mating I have chosen and, slowly, the more traditional stamp of dog is returning with each generation, while maintaining those three vital characteristics I mentioned before.

I very much doubt my lines will ever produce a show champion, but this is not something I am particularly concerned about. However, I feel it is important to honour the heritage and origins of the original dogs.

It is important that, when breeding, we all look at what our own lack. If they have the original stamp and are fit for purpose, do they have the necessary temperament? Perhaps they are stunning, but lack drive and ability, or even biddability.

All of the above are considerations that it is imperative no breeder ignores. I have spoken to many different sources on this topic and, through my research, have found dedicated breeders who are determined to bring the Labrador breed back closer to its origins — a dog that is of breed standard but is fully functioning and fit to do the job it was designed to do. One that can work all day in cold temperatures, sit quietly and patiently waiting for retrieves, but also hunt and flush when required.

There are some fine examples of dual-purpose dogs, you simply have to look for them. A good place to start is the BASC arena at Crufts. Working dogs there compete in the show ring. The stamp of dog is much more closely related to the original labrador seen in the early 1900s, when dual-purpose labradors were much more common.

In fact, it was the 2016 field trial class Crufts winner that caught my eye — not only because of his working ability, but his stunning looks. He sired my own stud dog — and Shooting Times front cover star — Keepa. He received a lovely critique, mentioning traits such as his “kind head and expression”, “excellent length of muzzle, firm topline and sound mover”. This particular dog qualified and ran in the IGL Championship the same year as he won at Crufts, demonstrating a true dual purpose.

It is easy for any breeder to get hung up on one set of characteristics. And many may well believe that certain dogs should not be bred from. While I understand this in part, it is important that we do not become so hung up on what is lacking that we simply stop or refuse to breed from those we considered to be deficient in something.

The origins of the Labrador breed can be found in the lesser Newfoundland dog

Gene pool

By doing this, the gene pool of Labradors will be greatly reduced and make inbreeding a bigger concern. Instead, everyone breeding should be looking for balance. Physically, the dog should be of a sound and balanced type, staying true to the breed standard where possible. But the temperament, health and ability must be deemed to be as important.

If the dog has a huge flaw, such as health or temperament issues, breeding should rarely be considered. However, if it is only lacking slightly then the dog that it is bred with should complement it, with the ultimate goal of producing an all-round, dual-purpose Labrador.

No one can tell someone else what they believe makes a beautiful Labrador. For me, seeing them do what they were bred for in a day’s work, seeing them comfort my children at home as their original temperament was designed for and observing them achieve competitively in their field of speciality will always make them the most beautiful dogs in my world.

Labrador perfection, according to the Kennel Club

- General appearance: Strongly built, short coupled, very active; broad in skull; broad and deep through chest and ribs; broad and strong over loins and hindquarters.

- Characteristics: Good tempered, very agile (which precludes excessive body weight or excessive substance). Excellent nose, soft mouth; keen love of water. Adaptable, devoted companion.

- Temperament: Intelligent, keen and biddable, with a strong will to please. Kindly nature, with no trace of aggression nor undue shyness.

- Head and skull: Skull broad with defined stop; clean-cut without fleshy cheeks. Jaws of medium length, powerful not snipy. Nose wide, nostrils well developed.

- Eyes: Medium size, expressing intelligence and good temper; brown or hazel.

- Ears: Not large or heavy, hanging close to head, set rather far back.

- Forequarters: Shoulders long and well laid back, with upper arm of near equal length, placing legs well under body. Forelegs well boned and straight from elbow to ground when viewed from front or side.

- Body: Chest of good width and depth, with well-sprung barrel ribs — this effect not to be produced by carrying excessive weight. Level topline. Loins wide, short coupled and strong.

- Hindquarters: Well developed, not sloping to tail; well-turned stifle. Hocks well let down, cow hocks highly undesirable.

- Tail: Distinctive feature, very thick towards base, gradually tapering towards tip, medium length, free from feathering, but clothed thickly all round with short, thick, dense coat, thus giving ‘rounded’ appearance described as ‘otter’ tail. May be carried gaily, but should not curl over back.

- Colour: The only correct colours are wholly black, yellow or liver/chocolate. Yellows range from light cream to red fox. Small white spot on chest and the rear of front pasterns permissible.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Shooting Times & Country

Discover the ultimate companion for field sports enthusiasts with Shooting Times & Country Magazine, the UK’s leading weekly publication that has been at the forefront of shooting culture since 1882. Subscribers gain access to expert tips, comprehensive gear reviews, seasonal advice and a vibrant community of like-minded shooters.

Save on shop price when you subscribe with weekly issues featuring in-depth articles on gundog training, exclusive member offers and access to the digital back issue library. A Shooting Times & Country subscription is more than a magazine, don’t just read about the countryside; immerse yourself in its most authoritative and engaging publication.