The countdown is on for The British Shooting Show – book tickets online today and save on gate price!

Health checks you must carry out before breeding Labradors

Q: “I am considering breeding from my young Labrador bitch but have to confess to being overwhelmed by all the advice I am getting. Any thoughts?”

Thoughts on breeding Labradors

A: First I would say that breeding from your only dog can be fraught and is not entirely without risk. If you are under the impression that she somehow must have a litter to improve her health, think again. You should have a good reason for wanting to breed from her; for example, to keep a puppy, carry on desirable characteristics, improve the breed generally or produce a puppy for a friend.

Before considering the multitude of testing that should be carried out on a prospective mum, please consider her suitability for Labrador breeding. Is her conformation of an acceptable standard? Is she too fat or are her legs too short? Do you look at her through rose-tinted spectacles? Is she affected by any of the health issues that are inherited but for which there is no test available? (The list is long but includes Addison’s and Cushing’s diseases, heart problems, skin allergies and epilepsy.) I

Is breeding from her likely to be detrimental to her welfare, especially her temperament? Also take into account your circumstances: do you have the time, the place, the financial ability and, most importantly, the stomach?

How to start

I would initiate the health screening process for breeding Labradors with an eye test, carried out under the auspices of the Kennel Club/British Veterinary Association (KC/BVA) Eye Scheme, because it is the cheapest and least invasive of the required tests. A fail here stops you in your tracks without further expense or risk. Testing should be carried out annually, so one should be done in the 12 months preceding the mating.

Hip and elbow assessments

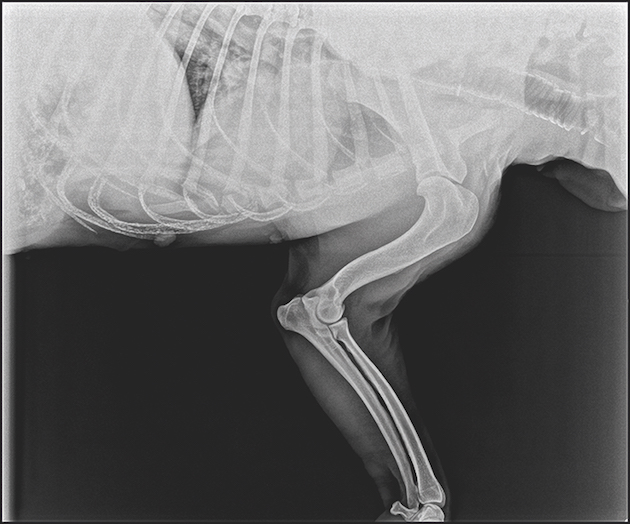

Next on the ‘must do’ list before breeding Labradors are hip and elbow assessments. Hip and elbow dysplasia are multifactorial abnormalities of development of the hip and elbow respectively. Both have a strong inherited element, especially elbows, though diet, exercise and luck also play a part.

The KC/BVA Hip Scheme involves general anaesthesia and X-rays of the hips, taken in a particular, precise manner. Dogs must be one year old or over. Each hip is scored from 0 to 53, so that the best hips have a score of 0 0 and the very worst 53 53. Beware of just being quoted a total score. Dogs should only be bred if their score is significantly better than the breed mean score and care should be taken in ‘matching’ dam and sire.

The Elbow Dysplasia Scheme requires lateral X-rays of both elbows, taken at 45- and 110-degree angles. Your vet would normally do this at the same time as the hip X-rays. Each elbow is scored from 0 to 3. It is imperative that only 0 0 elbows are bred from (that doesn’t mean 1 is OK). Having all the X-rays done, including the KC/BVA fee, will set you back a few hundred pounds and you can expect to wait a month or so for results (current circumstances allowing).

DNA testing

So your eye test is clear and your hips and elbows are looking good, now it is time for some DNA testing. Some conditions are caused by mutation of only one gene, so their inheritability is predictable. Multiple tests were required previously but the good news is that the Kennel Club recently launched a ‘combitest’, which, for one price (£135 including VAT with a 10% discount for Assured Breeders), allows a single DNA sample to be used for all the appropriate tests for an individual breed. For Labradors, these are:

- Centronuclear myopathy (CNM), a defect of the formation of muscle fibres that results in weakness, fatigue, difficulty eating and collapse.

- Exercise-induced collapse (EIC), a genetic disorder that generally affects otherwise fit dogs that deal with normal exercise without a problem. Strenuous activity, however, especially when associated with excitement, produces hind and sometimes foreleg collapse lasting 15 minutes. The problem lies with a protein that is involved in neurotransmission.

- Hereditary nasal parakeratosis (HNPK), an abnormality that causes the nose to dry out, leading to crusting, irritation, secondary infection and, over time, loss of pigment.

- Progressive retinal atrophy (PRA). The retina is the light-sensitive part of the posterior eye. Progressive rod-cell degeneration leading to PRA is one of a group of retinal disorders that start with loss of night vision and eventually result in blindness. Affected dogs show symptoms from three to nine years old, so potentially after they have been bred from. Retinal dysplasia is similar but causes abnormal development of the rod cells, so that blindness occurs early in life, at around two to three months.

- Skeletal dysplasia 2 (SD2), a form of dwarfism, known as mild disproportionate dwarfism, where the body is normal but the legs (especially the front legs) are too short. It seems its origin can be traced back to a single male labrador, born in 1966. Affected ‘big’ individuals can be difficult to distinguish from unaffected ‘small’ dogs.

For further advice I would suggest a few hours perusing the Kennel Club website. Remember that when agreeing to these tests being carried out, you also sign to allow the results to be published on the Kennel Club website. You can, therefore, check out the health status of any prospective sire, discover the world of Estimated Breeding Values and generally further muddy the waters by poring over pedigrees. Do not breed from untested dogs. Oh, and speak to your vet before committing to breeding Labradors.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Shooting Times & Country

Discover the ultimate companion for field sports enthusiasts with Shooting Times & Country Magazine, the UK’s leading weekly publication that has been at the forefront of shooting culture since 1882. Subscribers gain access to expert tips, comprehensive gear reviews, seasonal advice and a vibrant community of like-minded shooters.

Save on shop price when you subscribe with weekly issues featuring in-depth articles on gundog training, exclusive member offers and access to the digital back issue library. A Shooting Times & Country subscription is more than a magazine, don’t just read about the countryside; immerse yourself in its most authoritative and engaging publication.