The countdown is on for The British Shooting Show – book tickets online today and save on gate price!

Why does my Jack Russell hop, skip and jump?

There are two likely possibilities and I am afraid each might require a surgical intervention, which is not what you will want to hear.

Luxating patella

The patella, or kneecap, sits in the knuckle-like trochlear groove at the front of the thigh bone or femur. It has an important job. In a normal dog, it is attached above to the main muscle mass at the front of the leg, called the quadriceps, and below by the patellar ligament to the middle of the top of the shin bone or tibia. When the quadriceps muscle contracts, it pulls on the patella which pulls on the tibia and so the leg is straightened. Were the patella not a firm cartilaginous structure, but just a plain ligament, it would wear through in time.

In some dogs, usually because of developmental abnormality, the patella is unstable and inclined to dislocate out of its groove to a position inside the leg. When this occurs, a skipping movement is seen, with the affected leg being held up, as the pull of the quadriceps is thwarted. This can be permanent in advanced cases, but is usually transitory in younger dogs and is dependent on the degree of abnormality. Vets usually grade the problem from one to four based on palpation of the position of the patella but surgical intervention is only required if the limb is badly dysfunctional or the knee painful. The condition is most common in small breeds, such as Jack Russells, Chihuahuas and Yorkshire terriers.

It is caused by a combination of:

- Medial bowing of the leg

- Development of a very shallow groove

- Twisting of the tibia

- Rarely by trauma

Your friendly vet should be able to diagnose it quite easily. Corrective surgery involves slackening the inside capsule, tightening the outside, sawing off the attachment of the patella at the tibia and pinning it back to a central position and deepening the groove.

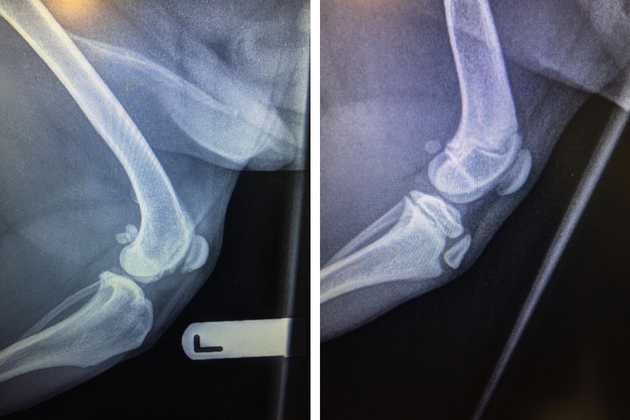

(Left) A young dog ‘s knee – the growth plates can look like fractures (Right) This x-ray of an older dog shows the patella at the front of the femur

Legg-Calves-Perthes Disease

This sounds complicated. And it is. Technically it is an aseptic necrosis of the femoral head and neck. It sounds sore and it is! The femoral head and neck form the hip joint as they articulate with the socket or acetabulum of the pelvis. In some dogs, generally small breeds from around five months of age, a disease process occurs, which damages the bone. The process is progressive and involves:

- Infarction/blockage of the arteries supplying the bone

- Lack of blood supply to the head and neck

- Deformity of the bone

- Cracks in the articular cartilage

- Degeneration of the joint

Clinical signs of this condition differ subtly from patellar luxation. It is usually noticed earlier. (Dogs affected by patellar luxation rarely present before six months.)

The femoral neck is disintegrating

Typically you would see:

- Progressive lameness

- Only about 10 per cent have both legs affected

- Pain on manipulation of the hip joint

- Restricted movement of the hip

- Muscle wastage around the hip

- Behaviour changes due to pain

- Crunchy feel on movement of the joint

Again your friendly vet should have a reasonable idea what is going on just by palpating the joint. Even nice dogs can bite you when you move the hip! Certainly, it is usually obvious that it is the hip and not the knee that is the problem, though it can be impossible sometimes not to move one joint without affecting the other. And, just to complicate the issue, we occasionally see dogs who have sub-luxating patellae AND necrosis of the femoral head and neck.

The diagnosis has to be confirmed by X-ray and I always have a heavy heart when I see evidence of the destructive process. Treatment involves (relatively expensive) excision of the damaged femoral head and neck, though I have had to amputate some legs because of severe muscle loss. The prognosis for a working terrier is not great.

I am afraid you need to hop down to your vets pronto!

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Shooting Times & Country

Discover the ultimate companion for field sports enthusiasts with Shooting Times & Country Magazine, the UK’s leading weekly publication that has been at the forefront of shooting culture since 1882. Subscribers gain access to expert tips, comprehensive gear reviews, seasonal advice and a vibrant community of like-minded shooters.

Save on shop price when you subscribe with weekly issues featuring in-depth articles on gundog training, exclusive member offers and access to the digital back issue library. A Shooting Times & Country subscription is more than a magazine, don’t just read about the countryside; immerse yourself in its most authoritative and engaging publication.