Even Guns who’ve spent many seasons standing on the peg or walking along hedgerows are sometimes unclear about some shooting…

★ Win a Schöffel Country shooting coat for everyone in your syndicate worth up to £6,000! Enter here ★

The modern cartridge vs the flintlock

If you have ever fired a flintlock, you will know that it feels as if the world has suddenly slipped into slow motion when you compare the experience to that of firing your modern shotgun.

When you pull the trigger on the flintlock, you are very aware of a sort of “click – fizz – bang” sequence, rather than the modern gun’s apparently instantaneous “bang”.

There are several reasons for this. Firstly, the cock (which is the hammer-like thing with the flint attached to its nose) swings through a very long arc before the flint makes contact with the steel frizzen to create the spark, which ignites the powder in the pan. Then there is the time it takes for the flame to pass through the touch hole and ignite the main charge.

Flintlock unreliability

And it is not only the time factor that makes the flintlock a bit of a pain, particularly when shooting at a moving target such as a bird. For a start there is the unreliability of the system. The powder in the pan can ignite, but the flame can fail to travel through the touch hole – the origin of the term “a flash in the pan”, which we still use today. Gunpowder could have been of dodgy quality too, and if you were aiming at a high target, burning powder granules could fall back into your face. This must have been uncomfortable, and down right dangerous if a burning fragment got into an eye.

Then there was the ever-present problem of a hang-fire, in which it seemed to take an age for the powder in the pan to ignite the main charge…

So, although the flintlock era lasted for a couple of hundred years, a better system was clearly needed.

Forsyth’s invention

By the time the year 1800 dawned, a number of fulminates had been invented. To you and me that means substances that burst into flame when you hit them. The first man to realise the potential of these substances in firearms terms was a Church of Scotland minister called The Rev Alexander John Forsyth, whose living was in the village of Belhelvie, just north of Aberdeen. One modern biographical website suggests that Christians would have been embarrassed by the fact that a man of God should have invented a means of killing people more efficiently, but for Forsyth his experimental work was more to do with duck shooting – a sport to which he was dedicated.

As a duck shooter, Forsyth was very much aware of the flintlock’s shortcomings. The puff of smoke from the pan scared off his quarry when he shot at sitting birds (clearly shooting ethics were different in those days), and, among other problems, flintocks were difficult to load on windy or rainy days.

To improve his gun’s ignition, Forsyth mixed fulminate of mercury with other chemicals and by 1805 had devised a new priming system he called the scent-bottle lock. This consisted of a small, enclosed container filled with his priming substance –small amounts being fed into proximity with the touch hole before each shot. One charge of his priming substance would last for up to 30 shots and, although the system wasn’t ideal, it led to a chain of ever-improving ignition methods.

Without the chain of events from Forsyth’s invention, the modern cartridge could never have been invented

Chain of events

Joseph Manton, among other gunsmiths of the era, made an ignition system of his own, and in 1922 the artist Joshua Shaw took out a United States patent on what we now know as the percussion cap, which fitted over a nipple to transfer ignition to the propellant charge.

Without this chain of events, which has been considerably compressed due to space restrictions, the modern cartridge as we know it, with its primer in the centre of its base, could never have been invented.

PRIMER MATERIALS

Primer materials such as Forsyth’s, which contained mercury compounds, left behind highly corrosive residues, which were distinctly unfriendly to barrels. Other mixtures, heavy on potassium chlorate, left a substance like ordinary table salt in the barrels, which called for very thorough cleaning after shooting. And once centrefire rifle and pistol cartridges became the norm, early primers attacked the brass, soon rendering cases unsuitable for reloading.

Modern primers use a substance called lead styphnate, which is more barrel-friendly. There are also some lead-free concoctions coming into use, but the military are a bit wary of them because there are claims they decay with age and, at best, don’t have totally consistent performance.

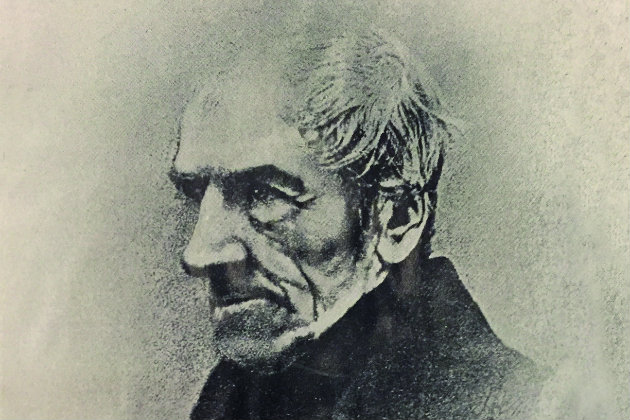

Reverend Forsyth

Eccentric Forsyth

A story told about the Rev Forsyth suggests that one day during his experiments he created an explosion so violent that he blew himself out through the door of his work room. Perhaps it’s my imagination gone into overtime, but I get an impression of Forsyth, his face blackened, his hair singed, and his clerical garb smouldering, staggering out into the street – to the huge amusement of his parishioners, who must have already regarded him as an eccentric…

In order to communicate with his parishioners, Forsyth would have spoken Scotland’s third language, Doric. It’s still spoken in my home village on the Moray Firth coast, where a typical greeting is: “Fitlike, Mike ma loon?” Or in English: “How are you, Mike, my man?”

Blackpowder, a home-made 8ft long punt-gun and muzzle-loading memorabilia …

On a warm humid day, the Bridgwater Bay Wildfowlers’ association brought the boom and sulphurous smell of blackpowder to the…

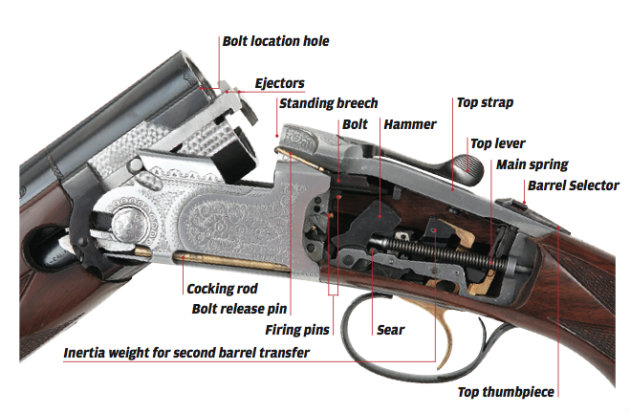

Do you know your boxlock from your flintlock?

On the other hand, if you’re flummoxed as to what they mean but you want to be taken as a…

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Shooting Times & Country

Discover the ultimate companion for field sports enthusiasts with Shooting Times & Country Magazine, the UK’s leading weekly publication that has been at the forefront of shooting culture since 1882. Subscribers gain access to expert tips, comprehensive gear reviews, seasonal advice and a vibrant community of like-minded shooters.

Save on shop price when you subscribe with weekly issues featuring in-depth articles on gundog training, exclusive member offers and access to the digital back issue library. A Shooting Times & Country subscription is more than a magazine, don’t just read about the countryside; immerse yourself in its most authoritative and engaging publication.