Gear

Shooting

Choosing a scope – 11 things you need to consider

Would you like to speak to our readers? We offer sponsored articles and advertising to put you in front of our audience. Find out more. Air gun product shot in the studio

Air gun product shot in the studio

While air rifles are certainly available with alternative sighting systems, notably open sights, it’s fair to say that the majority of shooters will be using a telescopic sight. But how do you go about choosing one? Finding one that comes within your budget is of course a major factor, but there are plenty of other things to consider.

A telescopic sight may well offer numerous exciting features, but it really has just one job to do, and that is to help us point the barrel of our air rifle in a particular direction so that when we pull the trigger, the pellet will fly through the air and hit the target in a predictable manner.

There are 11 factors that must be taken into consideration by an individual shooter who’s looking for a scope. And that last bit is important because this is about finding the right scope for you, not your buddy or some random bloke at the range.

1. Can you sharpen the reticle properly?

The ocular ring must be adjusted so the reticle looks sharp to the shooter’s eye – don’t confuse this with the clarity of the target image

Regardless of its design, which we’ll discuss in more detail later, the reticle needs to be in focus for the shooter, irrespective of the target that’s being viewed, the distance away from the target or the level of magnification that’s been selected. Our eyes are all different and we need to use the ocular focus ring to ensure the reticle is crisp.

You may need to unscrew a locking ring before you can make any adjustments. Once the focus ring has been set, the locking ring can then be secured, meaning the ocular focus ring can’t be moved by mistake. If no locking ring is present, the ocular focus ring is said to be a “fast focus” ring. This is quicker and easier to adjust, but because it can’t be locked in place it may get turned without you knowing it, in which case you’ll need to reset it to suit your shooting eye.

If you’ve chosen a prospective purchase and have worked your way through the whole range of adjustment and cannot get the reticle to appear sharp, walk away from it as you will never be able to shoot to the best of your ability with a scope like this.

2. Can you adjust parallax?

Parallax on this Hawke 3-9x scope is altered using an adjustable objective (AO) control at the front of the objective bell

Parallax is the effect whereby the position or direction of an object appears to differ when looked at from different positions. Parallax error therefore occurs when the object

is not viewed from the correct position.

In shooting terms, parallax error is an unwelcome phenomenon that’s usually associated with telescopic sights when the target image is not focused on the reticle of the scope. Parallax error can be minimised by keeping your eye central to the ocular lens for every shot you take, which is why maintaining a good, repeatable head position on your stock is so important.

Parallax error changes with distance, so you’ll need to readjust your controls every time you alter the distance over which you’re shooting. Most scopes can be adjusted for parallax, but some cannot. These will be set by the factory to be parallax-free at a certain distance, often at 50 or 100yds, which is of little use to airgun shooters.

If you are considering buying such a scope, find out at which distance parallax has been set and see if this ties in with the distance at which you are intending to shoot your rifle. Scopes offering no parallax adjustment usually do so for reasons of cost, but in my opinion it’s a false economy to buy a scope that does not offer some form of parallax adjustment.

3. Is the target image in focus?

Higher-end scopes like this Hawke Sidewinder offer excellent optical clarity and a crisp image of the target

When light passes through the lenses of a scope, not all of it will make its way through to the shooter’s eye. Nevertheless, perhaps because the shooter is focused so determinedly on the sight picture, the image often appears to look brighter. Better quality lenses can enhance the image, and will also help transfer more of the available light in lower-light conditions.

While optical quality is a highly desirable feature, it’s arguably of less importance for the typical airgun shooter due to the shorter distances over which we shoot. What is vital, however, is for the target image to appear as sharp as possible, regardless of the brightness of the image.

Adjusting parallax normally has the secondary benefit of making the target image look sharper and in focus. But some scopes will simply fail to deliver a sharp image, with the target looking blurry regardless of where the parallax control has been set. This indicates a major flaw in the lenses themselves, the way they’ve been arrayed or the general construction of the scope.

This flaw is not always obvious to spot until the scope’s been mounted to a rifle, but should you find one like this, walk away. While this problem is more often encountered on low-end scopes, I’ve seen a few costing over £500 that have exhibited this error, so beware.

4. Is it the right size?

This Hawke Sidewinder is designed for long-range work and is lengthy, but still suited to the R-10 SE that it sits on

The popularity of shorter air rifles has seen a demand for shorter scopes. Because these types of rifle are primarily designed for hunting, a range of short-bodied scopes has emerged that are designed to be looked through with minimal eye relief, but offering a wide field of view, typified by scopes like the MTC Viper Connect and Hawke Airmax Touch.

A wider field of view makes it easier for the shooter to acquire and track a target. It’s not just hunters that benefit, as target shooters in fast-fire disciplines need fast target acquisition.

Another type of optics, such as the MTC SWAT, reduces the length of the optic even further. While an ordinary scope relies on the various lenses to transfer the light to the shooter’s eye, these scopes use a prism to refract it, which means the scope can be made much shorter.

Scope length is of even more importance for the springer or gas-ram shooter. A telescopic sight that’s too long can overhang the pellet loading bay on an underlever and an overly long scope that’s been fitted to a break-barrel can overhang the breech and prevent the rifle from being cocked.

5. Side parallax or adjustable objective?

It’s easy to adjust parallax while in the aim using a side control as with this MTC Copperhead, making the image nice and clear as a bonus

Having discussed the importance of eliminating parallax error, let’s discuss the control system. The adjustment control can take the form of a ring around the objective bell, in which case the scope is said to have an ‘adjustable objective’ or ‘AO’. Alternatively, the parallax control can be mounted in a turret on the left-hand side of the scope saddle. Scopes with this feature are said to have a ‘side parallax’ control or be ‘side focusing’.

Parallax controls will be graduated in either yards or metres. These graduations are helpful, but adjusting the control until the target image snaps into focus is of more importance than trying to adjust them by relying on the distance markings.

Some scopes with side parallax come with no distance markings at all, letting the shooter stick on their own markings, having calibrated the scope at different distances in their preferred choice of either yards or metres.

AO is the more traditional means of adjusting parallax, and scopes using this system tend to be a bit cheaper as this system is easier to manufacture. Adjusting an AO scope is not always easy, especially in the aim as you have to reach forward to turn the control. In addition to being more physically awkward than the side parallax type, such a movement may spook quarry.

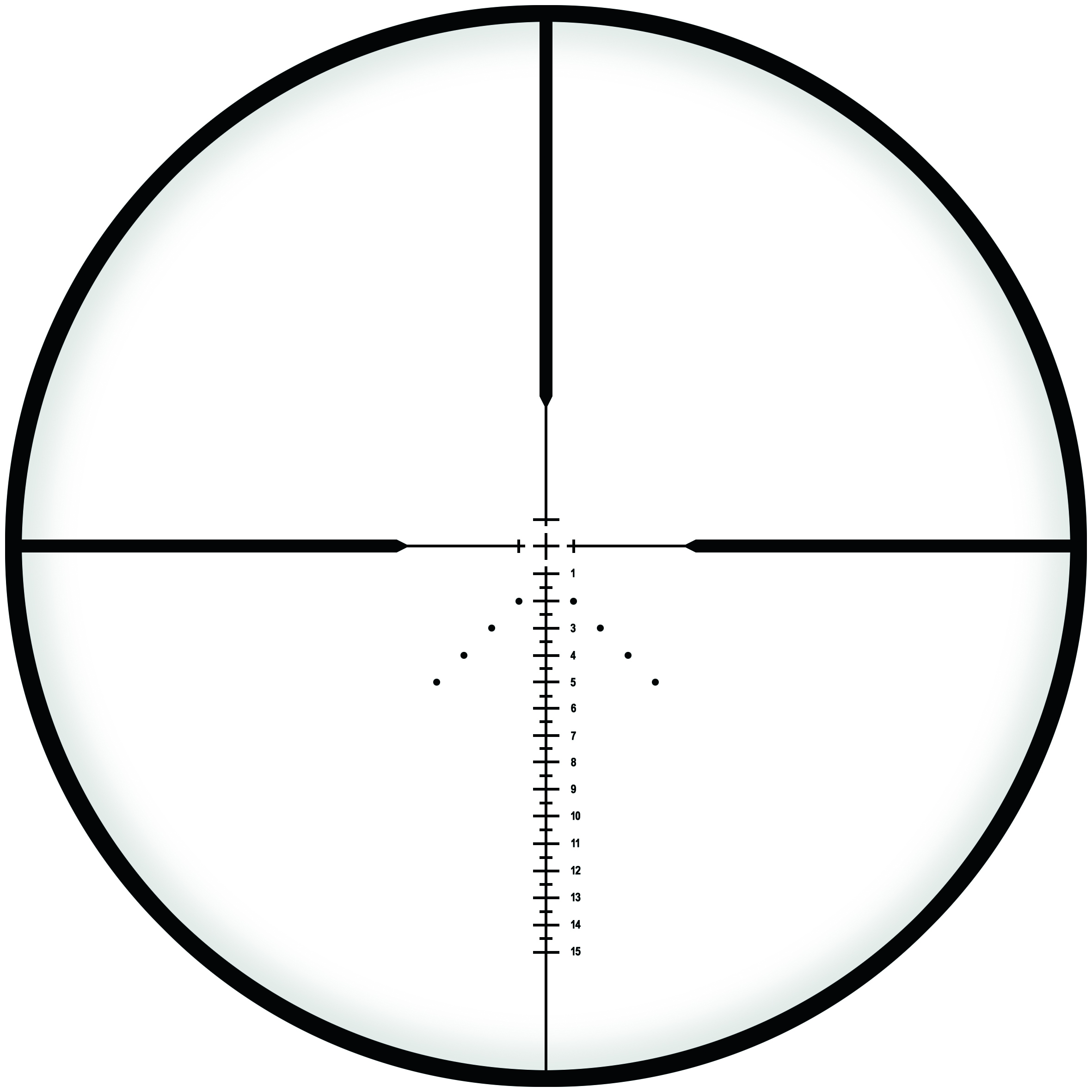

6. Is the reticle right?

This reticle is MTC’s Advanced Mil-Dot (AMD2) design, which offers plenty of aim points while keeping the sight picture relatively clean

The scope body contains an assembly called the erector tube which holds the magnification lenses and reticle, also known as ‘reticule’ or ‘crosshairs’. ‘Reticle’ is the most common term, as the word reticule also refers to a type of ladies’ bag from the Regency period. The term ‘crosshairs’ relates to the fact that early reticles were made from crossed fine wires, fibres or hairs. Nowadays most reticles are created using engraved lines, hence the term glass-etched, or embedded fibres.

What’s of more importance, however, is the amount of detail available to the shooter in terms of suitable aim points, when taking into account the need to aim off for ballistic drop or wind drift. Choose the reticle for your needs. A Duplex reticle may be all you need if all your shooting is carried out at the same distance the rifle was zeroed at, as in disciplines like Light Sporting Rifle or Benchrest.

But most other types of shooting will require a more complex reticle, allowing for holdover and holdunder. The level of complexity comes at a cost in terms of how easy the reticle is to use and how quickly you can acquire the target with the correct point of aim. If you don’t need the features of a multi-aim point reticle, then you may be better off with something less cluttered.

7. Do the turrets match the reticle?

The Copperhead’s AMD2 reticle is a mil dot type, and each windage and elevation turret click represents 1/10 of a milliradian

Most reticles that offer alternative aim points will be graduated in either MOA (minute of angle) or mils (milliradians). The MOA system has been overtaken by mils these days, a result of its adoption by the military and the fact that scopes in service with the armed forces have ended up working nicely in civilian hands.

One thing that’s not always done well is matching the graduations of the reticle to the turret controls. Some scopes with a mil reticle will have turrets that adjust fall of shot by ¼ MOA per click. This makes it harder to work out how many clicks you need to adjust by. In contrast, if the reticle is in mils and the turret clicks are 1/10 of a mil, it’s simple to work out how many are needed to make point of impact coincide with point of aim. Are mismatched reticles and turrets a dealbreaker? Not for most airgun shooters, but it’s worth being aware of.

8. Do you need an illuminated reticle?

This reticle is illuminated with six levels of brightness in red, with the IR control on the left-hand of the saddle, outboard of the parallax control

Some scopes will have an illuminated reticle. The description of some scopes will include the term “IR”, which in this case means illuminated reticle rather than infrared. An illuminated reticle is a battery-powered feature which will light up the reticle in varying intensities, usually in red, but sometimes in green or blue. Some have the option to switch between colours.

Illuminated reticles are typically used to highlight the reticle in the shooter’s eye in low-light conditions, but they can be useful when you’re trying to place your black crosshairs over a target in the field that’s in dark shadow, or lie them over a black target at the range. Scopes offering this feature may have a dedicated turret for illumination, or it may be built into an existing control such as the side parallax turret.

I wouldn’t buy or reject a scope on the strength of it having an illuminated reticle or not, but it is useful to have, even if you don’t use it all that much, and can also help some people who have eyesight problems. The downsides are extra expense, additional bulk and the need to change batteries in an otherwise purely mechanical optical instrument, although they do last a long time.

9. First or second focal plane?

As magnification increases with an FFP scope like this Hawke, the size of the reticle also increases, along with the object being viewed

The terms first focal plane (FFP) and second focal plane (SFP) refer to the location of the reticle in relation to the magnification lenses inside the erector tube. Where the reticle is positioned will affect the way shooters see their target as they adjust magnification.

With an SFP scope, the reticle is positioned behind the magnification lens. This means the size of the reticle will stay the same when magnification is increased or decreased, while the size of the image being viewed will expand or contract accordingly.

With an FFP scope, the reticle will be mounted in front of the magnification lens. This time, when the level of magnification is altered, both the size of the reticle and the size of

the target image will change but remain in proportion to one another.

These distinctions are important if you use holdover or holdunder to hit your target at varying ranges. In the case of a second focal plane scope, your set of aim points will only be accurate at one particular level of magnification, while for a first focal plane scope the aim points will always remain true, regardless of the level of magnification you’ve selected.

10. Does it have enough magnification?

How much magnification you require will depend on the type of shooting you do, with higher mag settings offering more precision

Most scopes for airgun use offer a range of magnification. The magnification lenses inside the erector tube move when the scope is being adjusted, going towards the objective lens when the shooter is increasing magnification, and moving towards the ocular lens when reduced.

Scopes offering variable magnification will have a control called the magnification ring, also known as the ‘power ring’, to adjust magnification. The ring is located at the front of the ocular bell. The magnification ring should be marked and, like any scope control, turn smoothly.

Some second focal plane scopes may have one power level highlighted in a colour, typically red. This feature is usually found on scopes using a reticle graduated in milliradians, and a mil as seen in the reticle of an SFP scope will only be “true” at one magnification. How much magnification you need will depend entirely on the type of shooting you do, with target disciplines such as FT and Benchrest demanding the highest level of magnification. Lower levels of magnification bring their own advantages in terms of clarity of image, field of view and faster target acquisition.

11. Weigh it all up

The traditional advice to spend as much as you can afford on a scope still holds true, but advances in manufacturing techniques mean fewer genuinely poor-quality scopes are on sale today and it’s never been easier to get hold of a good, dependable optic for less financial outlay.

When you draw up a shortlist of potential purchases, think about the type of shooting you do and whether the features offered by one particular scope will fit in well with your style of shooting. And if possible, try before you buy. A good optic will carry on working for years. But whether you keep it for years depends on whether you bought the right one in the first place!

Related articles

Gear product reviews

Science in colour

The art of concealment is the hunter’s superpower and camo plays a huge role

By Time Well Spent

Gear buying guides

Top stalking layers to beat the heat

Chris Dalton discovers five garments designed to cope with frosty starts to midday heat.

By Time Well Spent

Manage Consent

To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us to process data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

Functional Always active

The technical storage or access is strictly necessary for the legitimate purpose of enabling the use of a specific service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user, or for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of a communication over an electronic communications network.

Preferences

The technical storage or access is necessary for the legitimate purpose of storing preferences that are not requested by the subscriber or user.

Statistics

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for statistical purposes.

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for anonymous statistical purposes. Without a subpoena, voluntary compliance on the part of your Internet Service Provider, or additional records from a third party, information stored or retrieved for this purpose alone cannot usually be used to identify you.

Marketing

The technical storage or access is required to create user profiles to send advertising, or to track the user on a website or across several websites for similar marketing purposes.