Night of the long dogs

A rainy and foggy night in the Yorkshire Dales promises little rabbit action but lamping with lurchers proves a success, says Matt Cross

Molly watches the light intently as Andrew sweeps the beam across the field

Taking lurchers lamping

At the end of the beam, Blue turned hard, just inches behind the rabbit. It turned too and again Blue went with it, heeled over like a racing yacht. The rabbit made a last, desperate twist then Blue was trotting steadily back to Jake, the rabbit held firmly in his mouth.

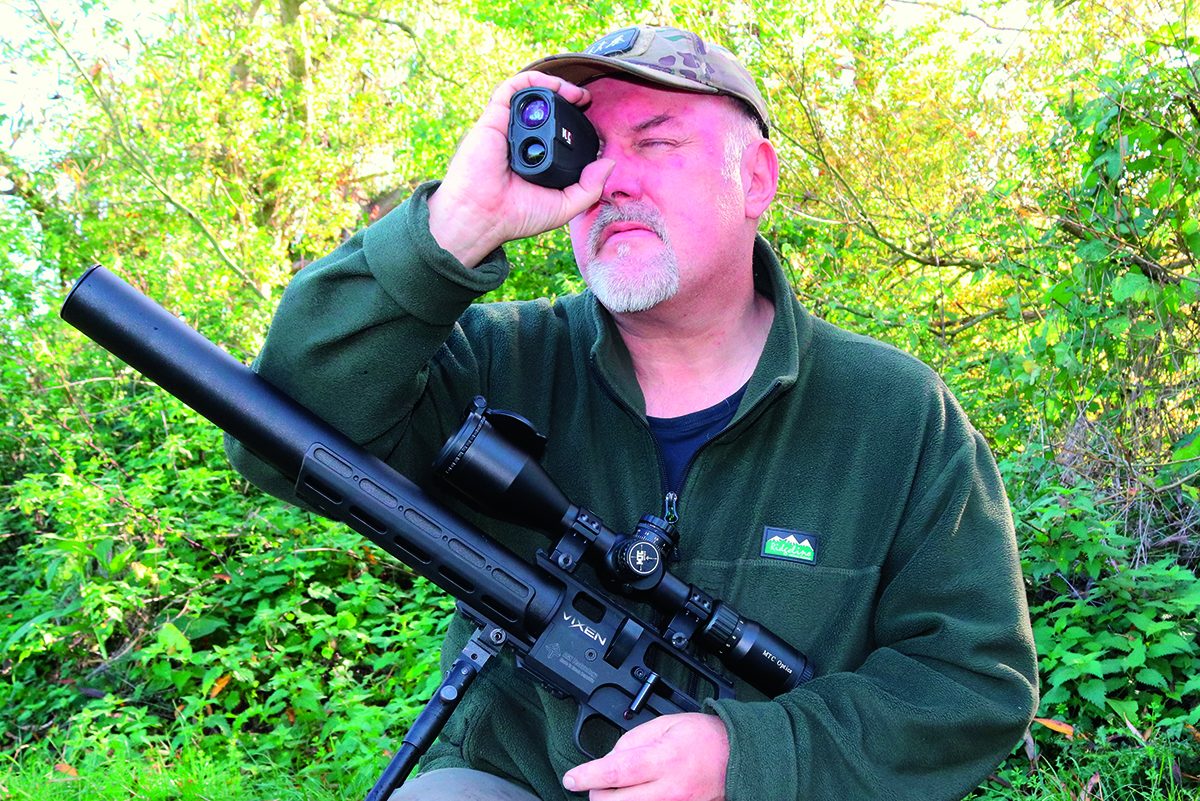

We had met on a damp, rainy night in a small town in the Dales. Jim Nicholson had brought Bo; Jake Taylor, a council animal welfare officer, had Blue; and roofer Andrew Hayes had Molly. Andrew, a keen, all-round country sportsman, found himself briefly famous when a petition he launched to have Chris Packham sacked from the BBC attracted 140,000 signatures.

The three men have worked hard to build up their reputations as honest and effective rabbit controllers. The outcome of their work is that they have permissions across Yorkshire, giving them thousands of acres to shoot and run their dogs and a network of butchers and game dealers keen to take the meat.

Taking lurchers lamping has a certain reputation, a rough sport that to some is synonymous with poaching. Leaving the small Yorkshire pub where we had met, someone remarked that we looked as if we were up to no good. “Got some lurchers?” he asked. When Jake answered that we had, he seemed to have found his confirmation: “Definitely up to no good then.”

It’s a shame that the lurcher has this reputation. It is the truest of hunting dogs, an animal bred purely for function, no gilded certificates nor curious abbreviations and no tests or trials other than its ability to catch game. No lurcher will ever be seen in the ring at Crufts, but dogs such as these have a far longer history than most breeds. You will find references to them in the Norman forest laws, woodcuts of them in the 17th century, and deep in Cairngorms there is a tumble of rocks called Creag an Leth-Choin — the crag of the half-dog named for a lurcher that lived so long ago its story has passed from memory.

A lurcher is, by definition, a cross-breed. Blue is a classic type, a whippet-collie cross. The whippet blood brings speed and manoeuverability and the collie brings the all-important intelligence and trainability. The other two dogs hunting that night are a cross that I had never previously encountered. Sisters Bo and Molly were half greyhound and half kelpie.

Lamping with lurchers

Hostile terrain

The kelpie is a leather-tough Australian herding dog, bred to gather sheep and cattle on some of the most hostile terrain on earth. Their ferocious intelligence is the product of generations of work driving half-wild brahman cattle across the outback, a job that would have killed or broken dogs that could not think for themselves. Crossing them with a greyhound results in a fast dog that can read and use the terrain ahead of it, can live in a kennel and does not suffer during a cold wet night’s lamping in the Yorkshire Dales.

I can’t be more specific about precisely where, because we arrived in the dark at the end of maze of country roads at a gate that could have been anywhere. Jake stood pointing into the darkness and naming the grouse moors that surrounded us. I’m sure he was right but in that pitch-black night it was hard to imagine great rolling expanses of heather.

The night was not just dark, it was also wet and, far worse, foggy. The water-filled air blocked and spread the lamp beams, turning them from long-range spotlights into something more akin to floodlights. It was with little hope of a big bag that we set out.

The three dogs and their handlers spread out across the first field and began to work their lamps. I went with Jake and Blue. By Jake’s estimation, the dog has caught more than 600 rabbits and he knew what was afoot. His ears were pricked, his body strained forward and his eyes were focused down the beam. Despite the conditions, it did not take us long to find our first rabbit.

Blue darted down the beam, turning hard on the heels of the racing bunny. He gathered it and and delivered it alive and undamaged to Jake, who swiftly despatched it. For a few fields, the action slowed and the night was quiet and misty, making the rabbits nervous and keeping many below ground. The lamps also struggled to pick out what rabbits were there in the thick fog.

When a field had been searched, the three hunters joined back up before deciding on how they would tackle the next one. By spreading out, they were able to use their lights to steer fleeing rabbits to one another. While all three were proud of their dogs and wanted to see them do well, co-operation, rather than competition, was the order of the day.

Real action

As we dropped down, we slipped out of the fog and the real action began. On one large rush-filled field I joined Andrew and Molly. At first it looked as if the action would be slow, but soon we had a rabbit in the lamp and Molly was tearing down the beam towards it.

It made for a drystone dyke and Molly, reading the situation, positioned herself to turn it away from safety. It was the real lurcher way — the greyhound’s speed and the herding dog’s instinctive ability to read and manage the animal it was pursuing. On another night, the rabbit’s manoeuvrability and knowledge of the terrain might have got it to safety, but not tonight.

As we worked across the field, the bag was steadily building. Andrew, Jim and Jake take so many rabbits in a year that they designed their own rabbit-carriers and had them made by Ian Nelson of Nelson’s Net Loft. Unlike the braided cord affairs that can be bought on the internet, these used thick webbing, snap buckles and metal holders for the rabbits that allowed a big haul to be quickly loaded and comfortably carried.

Blue makes another cracking run to bring a bunny straight to hand

Professionalism

It came as no surprise to me that Andrew, a roofer, wanted the most efficient and best-organised gear he could. On a roof, such equipment that doesn’t get dropped or forgotten allows for speedy and efficient working and Andrew brought this professionalism to his rabbiting. He didn’t want to faff around loading rabbits in a fiddly carrier when he could be working his dog.

As the team started to gather again, Andrew sent Molly over a fence. She cleared it with ease and darted after the rabbit. It ducked under the fence to the side where Molly had started. Over she went again, hot on its heels — the rabbit turned again and dived under the wire. Molly followed and the bunny, clearly believing this was its best chance, made another dive through the fence. This one threw the dog, who ran on. Unfortunately, it ran smack into Jake’s light and Blue’s waiting mouth and was soon added to Jake’s already well-stocked rabbit carrier.

We coursed on, covering miles of rough wet country. Walking with Jake again, he sent Blue for a rabbit that sat with apparent nonchalance, sidestepping neatly into a hole in the roots of a tree just as the dog arrived. In the lamp beam I swear there was a look of total bafflement on the dog’s face. Jake was less puzzled — he simply put his hand down the hole and pulled the rabbit out.

At last we came back to the road. We stashed the caught rabbits behind a wall for collection later and began our walk back to the car. As we walked, we searched the roadside fields. Jim picked up a rabbit and sent the veteran Bo over the wall. What, to my inexpert eye, looked like one of the best courses of the night ensued. Bo held tight to the rabbit as it sprinted for the cover of the rushes, splashing up water from its frantic bounds. It turned hard, weaving through the rushes and Bo stayed with it. It twisted through the thick clumps, drawing a crazy pattern, but it could not shake the dog. It broke cover and found it again. It was a battle of speed and agility and just out of sight the dog won, jumping the fence with the rabbit in its jaws.

Even when the action slowed, the grouse moors and game shoots ensure that there is a rich supply of wildlife. There were brown hares, which were left to go about their business, fieldfares, snipe, an unexpected golden plover and even a wandering grouse that let us walk within touching distance.

So what is lamping?

Lamping is a simple procedure of shining a light around an area until a rabbit (or rat) is spotted, and…

Lurchers: the best dog for rabbiting

Lurchers are not a breed as such but a ‘variety of types’ arrived at either by accident or design for…

We finished the night with 26 rabbits. One showed a touch of myxomatosis, another had an ugly abscess, but the remaining 24 were perfect, healthy beasts. Ian gutted them with extraordinary speed and efficiency. I took four for the table and the remainder were heading to a traditional butcher who found a ready market for them.

Taking lurchers lamping had brought a fine night of sport that resulted in a reduced pest population and a good haul of fit, clean rabbits for the table, which is a fine tribute to the dogs and the men working them.