Win CENS ProFlex DX5 earplugs worth £1,149 – enter here

Shooting corvids: Why our corvids are all going raven mad

Corvid Pest Control To Protect Wildlife

Corvid Pest Control To Protect Wildlife

Overall, our corvids are doing well these days. Even the recent modest decline of the rook should be set in the context of a largely increasing picture since the 1930s. The rarest, the chough, is now given green status in the current British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) listing, having staged a modest recovery from a very low ebb. In south Wales they have spread back along both the Ceredigion and Bristol Channel coast from Pembrokeshire, including reappearing on the Gower Peninsula, west of Swansea. There is much celebration that they have recolonised Cornwall too, with several pairs now nesting there, and numbers growing.

Wild grey partridges across the country benefit from meaningful predator control

Shooting corvids

At the other end of the numbers spectrum, the jackdaw is reckoned to be our most abundant corvid, with an estimated national population of 1.4 million pairs, a 75% increase over the past 25 years. This increase seems to be mirrored on my own patch, where we have more than ever nesting in the nooks and crannies about the old brick and flint farm buildings. Indeed, they have become a serious pest in relation to free-range poultry, taking significant amounts of food, as well as any eggs that are not laid in the safety of the henhouse.

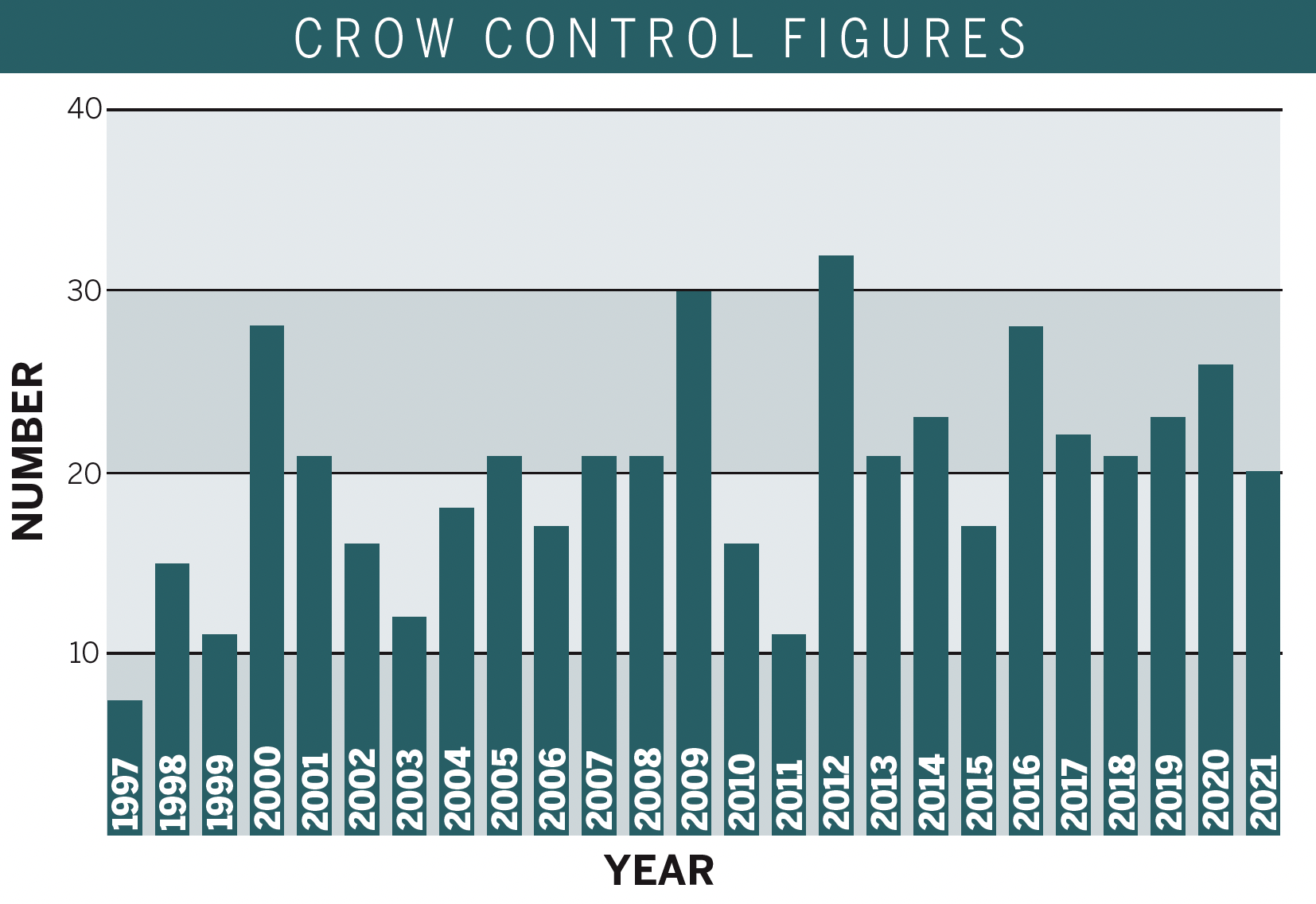

Mike’s tally of crows has remained steady over the past 25 years and 2022 looks to be on track

So I decided that a quiet creep about the yard and buildings might give me the chance of shooting corvids, to nobble one or two, or at least dissuade them a bit, even if I was very unlikely to dent the population. Sneaking around the end of the buildings, I spotted one in range, and let drive. Now we all know that flying corvids look ponderously slow and that is my excuse for the fact that I missed behind, clipping off half a tail feather for proof.

The general licences allow corvid control for the purpose of preserving wild birds or protecting livestock and feedstuff

The rest of the birds flushed and flocked up pronto, without offering a shot, retreating to sit in the crown of a dying ash tree a couple of hundred yards away. There they could survey my every move, remaining entirely impregnable to any approach. Nevertheless, I decided on a patient wait outside the old walled garden, where a few bushes and trees gave me a bit of extra cover. After a while some of them began to drift away, but none in my direction.

As I was about to give up, a miracle happened; a crow that was clearly just minding its own business came across from the west. This time I gave a proper lead and down it came. Being someone who relies mainly on Larsen traps for crow control, I hardly ever shoot one, so adding this bird to the season’s tally was very satisfying. Gathering up the crow, I decided it was now time to abandon the jackdaw project. Any that might have forgotten where they last saw me would surely now have been reminded. I decided it was time to stop shooting corvids and to go and check my traps. (Read more on Larsen traps here.)

Mike Swan’s three Larsen traps have caught a steady number of crows over the past 25 years

Stoat and weasel

For someone who is trying to look after a modest population of wild grey partridges, accounting for a crow makes a good day, so mine turned into a red-letter one when one of my three Larsens had caught, too.

Tunnel trap with caught stoat

That brace of crows made my total up to 19 for the season of shooting corvids, but there was more good news. I do not run that many tunnel traps — because I simply do not have time — but a rat in a New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC) 150 trap set against the outside wall of ‘gamekeeping HQ’ was another good result. The addition of both a weasel and a stoat made this a red-letter day indeed. (Using traps and snares – how to do it legally and effectively.)

When the ravens first showed up here, I wondered what would happen to the numbers of other corvids. Guilds of predation being what they are, I speculated that the next size down, the carrion crow, might be suppressed by a combination of competition and nest predation, but I was wrong.

My annual crow tally has remained very steady over the past 25 years. Apart from a slightly slow start, I have averaged just over 20 a year, so this year’s tally of 19 so far is bang on course.

A rat in a New Zealand DOC trap is a good start to what turns out to be a red-letter day

Across the country, both carrion and hooded crow numbers have remained steady over the past 20 years, but the BTO’s common birds census suggests a fairly steep growth in numbers between 1960 and 1990. What drove this is hard to fathom, though the decline in both gamekeeper numbers and wild bird keepering may have something to do with it.

There is a recent scientific paper that correlates crow densities with pheasant rearing, suggesting that areas where higher numbers are released have more crows. This is all very plausible, and it could just be that extra pheasant carrion helps to support crows, but correlation alone does not show cause and effect, despite what our detractors claim.

The same paper suggests that jay numbers are higher with releasing too, but its harder to figure a link for this. Jays are not carrion feeders, though I guess they might be pinching pheasant food. On the other hand, perhaps the connection is to do with trees; crows and jays are both woodland birds, and most pheasant releasing happens in woods too. (Read more about the jay).

Magpies

Magpies are doing well, too, mirroring the crows in terms of growth and stability at the national level. That said, I don’t get them on the shoot like I used to. Once upon a time, I would trap similar numbers to the crows, but these days it is hardly worth the bother of setting one in a Larsen trap. This season’s score is a pair and I’m not failing to see or catch them — magpies are too obvious for that.

Mike spends a fair bit of time on avian predation control around the farmyard

Bottle

Perhaps there is a clue in the only raven that I have caught. I had expected to see them as a by-catch in my crow traps, but no, the one that I caught and liberated came to a magpie decoy. Perhaps that predation guild is working at the magpie level, and they are the ones that the ravens suppress? I don’t know, but I speculate that despite that great big beak, ravens don’t quite have the bottle to face a pair of crows.

Whatever, it is time that the world’s bird lovers begin to recognise more clearly that you cannot have more of everything and that shooting corvids is necessary. Wherever there is a species in the ascendancy, it is likely that one or more others are paying a price through competition or predation or both.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Shooting Times & Country

Discover the ultimate companion for field sports enthusiasts with Shooting Times & Country Magazine, the UK’s leading weekly publication that has been at the forefront of shooting culture since 1882. Subscribers gain access to expert tips, comprehensive gear reviews, seasonal advice and a vibrant community of like-minded shooters.

Save on shop price when you subscribe with weekly issues featuring in-depth articles on gundog training, exclusive member offers and access to the digital back issue library. A Shooting Times & Country subscription is more than a magazine, don’t just read about the countryside; immerse yourself in its most authoritative and engaging publication.