News

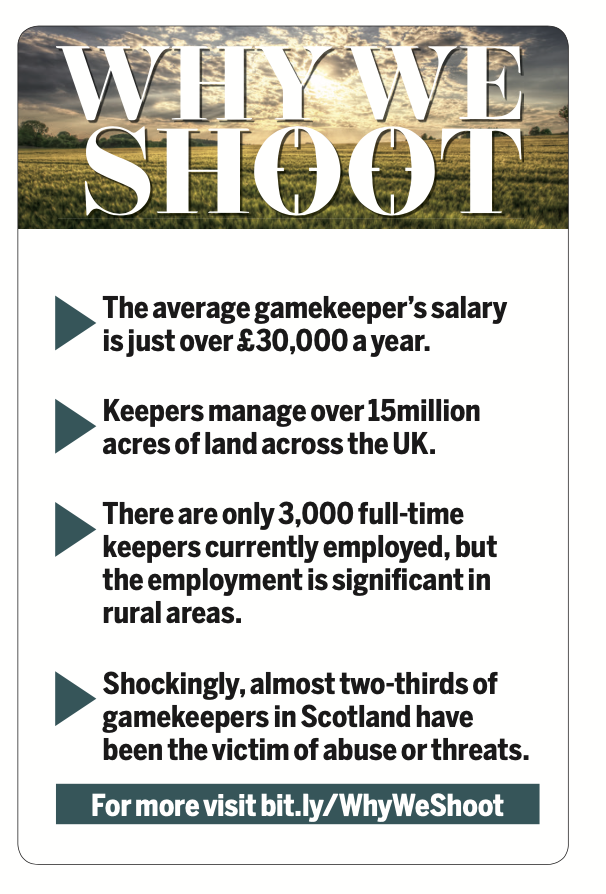

Gamekeepers suffer abuse on a daily basis – so what’s to be done about it?

Would you like to speak to our readers? We offer sponsored articles and advertising to put you in front of our audience. Find out more. Charles Forbes Adams

Charles Forbes Adams

The moderators were quick to pull the comment down, but I doubt they managed to do it before at least one of the many gamekeepers in the group had read it. It had been posted on a thread discussing grouse shooting on one of the large rewilding groups on Facebook. The commenter asked “Why don’t we stop hunting grouse and just hunt gamekeepers and their Tory bosses instead?”

The cyber abuse of gamekeepers has reached shocking proportions. Join an online rewilding group or scrutinise the comments section of one of the big anti-shooting blogs and you will find endless abuse of gamekeepers and gamekeeping.

The abuse is not limited to anonymous internet trolls. Celebrities have thrown their weight behind it. Before a new BBC director-general pushed him towards moderation, one of shooting’s leading opponents told a protest in London: “We’ve had it with snares, lead shot, illegal persecution; we’ve had it with a lack of scientifically informed decisions and animals being ripped to pieces with dogs; we’ve had it with our dwindling wildlife being wasted by psychopaths.”

Of course, the polished and media-savvy faces of the anti-shooting movement know they can’t call for harassment and abuse. But it is their rhetoric that creates the environment in which more extreme voices feel safe to speak out.

On the ground this has turned into real action that affects people’s lives.

The days when a respected gamekeeper could relax in his local pub appear to be long tone

Abuse of gamekeepers

Working on a story in Yorkshire a couple of years ago, I met an astonishingly cheerful man called Sam. He was a moorland gamekeeper on a syndicate shoot who did his rounds with a bull mastiff to keep him safe. “It’s endless,” he told me. “In the summer it’s every day. Quieter in the winter, mind. They don’t like the bad weather.” The ‘it’ he was referring to was harassment, disruption and abuse. He drew a distinction between “proper antis” and the “part-timers”.

Proper antis were the people who came on to the shoot at night, opened his pens, released his call birds from the Larsen traps, cut the lines to his drinkers then appeared on shoot days with depressing frequency.

Social media has become a valuable tool for abusers to spread hate and anti-shooting material

The part-timers were the runners and mountain bikers who shouted abuse at him when they happened to see him. A request for a jogger to keep to the footpath was met with an angry rant about the impending “extinction of the Harris hawk”. He was clear that this daily harassment was the product of the constant demonisation of gamekeepers and gamekeeping by prominent campaigners. But somehow he just shrugged it off: “I just go home and put my feet up.”

Sam’s resilience was remarkable but it is not universal. For many the constant wear of criticism has begun to show, as highlighted by a report for the Scottish government surveying keepers. It found that “many of the respondents reported feeling vilified by mass and social media sources, which can lead to work stresses, incidents of verbal and physical abuse and wilful damage of property”.

Helen Benson of the Gamekeepers’ Welfare Trust (GWT) knows more about this than almost anyone else. She said: “Increasingly there are calls to our helpline around abuse and pressure from the anti movement. Sometimes harassment of family, online or physical confrontation and a public campaign on individuals which can be vicious. There are groups and individuals who will stop at nothing to point the finger at keepers, and this is a pressure that every keeper is fearful of — someone finding ‘apparent evidence of wrongdoing’ and being deemed to be guilty, not ‘innocent until proven guilty’.”

In 2018 I was discussing an alleged case of raptor persecution with a gamekeeper in Highland Perthshire, when he told me of his approach: “I work with the idea that everything I’m doing is being filmed. From the moment I go out of my house to the moment I come home. I know they are after me.”

That would sound like paranoia if it weren’t for the fact that in 2018 a trail camera was found on an estate in Grampian covering the front of a gamekeeper’s house. A man, his face partially concealed by a mask, was later filmed recovering the camera. Not far away, GPS tracking equipment was also found.

Commenting on those cases of abuse of gamekeepers Lianne MacLennan, spokesman for Scotland’s Regional Moorland Groups, said: “It should be everyone’s right to work without fear. That is no longer the case for a gamekeeper in Scotland. The abuse of gamekeepers, the strain on them, their partners and kids would not be tolerated in any other walk of life.”

With the solitary nature of the job, keepers can feel even more isolated

Allegation

A while later I spoke to another keeper in the central Highlands, whose estate had been very publicly accused of being involved with crime. It was an utterly baseless allegation; not only was there no evidence he had done anything wrong, but also there was no evidence a crime had even been committed. Nevertheless, the story had been widely spread across newspapers and television. He had not only had the pressure of police questioning and searches, but then found himself on the receiving end of a torrent of abusive emails and even phone calls.

The stakes are also higher for gamekeepers than they are for most of us because, while the picture is slowly changing, most keepers still live in tied houses. Helen explained what is at stake when a keeper is hounded out of their job: “Housing is a huge issue for the keeper who loses his or her job with working dogs and a family, and often 200 applicants for each job. All these fears can combine to cause pressure and worry.”

Keepers have been filmed going about their daily routine

The gamekeeping team at Moscar in Derbyshire has perhaps been subject to the most concentrated campaign of harassment. An extremist animal rights team drawn from the hardcore of hunt saboteurs has turned an unrelenting focus on them. They have been filmed and photographed going about their work and the images have been spread online. In a Facebook post, one of the estate’s keepers was named and a photo showing his face was published.

Abuse of gamekeepers on social media

More than 250 abusive comments were published below the picture, many using the most extreme language that can’t be repeated, but “stick the barrel up his rear and pull the trigger. Bye bye scum bag” is typical. Dominic Dyer, minister for welfare in Chris Packham’s people’s manifesto for wildlife, praised the team’s “great work”.

Fortunately for gamekeepers and other wildlife professionals, when the pressure gets too much Helen and her GWT team are there.

She explained what the Trust can do: “GWT helps in a variety of ways, first and foremost by being available 24/7 through Jamie’s Helpline [0300 1233088]. Knowing there is someone who cares and will listen can be really helpful and alleviate the feeling that there is nowhere to turn.”

Keepers are facing pressure in a way they have never experienced before. Celebrities use their status to demonise them, on the ground activists harass them and on social media threats and intimidation have become routine.

Helen and her team at the GWT, and the support of fellow keepers and the shooting community, have never been more vital. Have you, or someone you know, been targeted for abuse? Let us know at STletters@futurenet.com

Related articles

News

PETA attacks royal couple for breeding cocker pups

The Prince and Princess of Wales have faced criticism from animal rights group PETA after they had a litter of puppies

By Time Well Spent

News

Farmers launch legal review against Reeves’s farm tax

Chancellor Rachel Reeves faces a judicial review over inheritance tax reforms that could force family farms out of business

By Time Well Spent

Manage Consent

To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us to process data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions.

Functional Always active

The technical storage or access is strictly necessary for the legitimate purpose of enabling the use of a specific service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user, or for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of a communication over an electronic communications network.

Preferences

The technical storage or access is necessary for the legitimate purpose of storing preferences that are not requested by the subscriber or user.

Statistics

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for statistical purposes.

The technical storage or access that is used exclusively for anonymous statistical purposes. Without a subpoena, voluntary compliance on the part of your Internet Service Provider, or additional records from a third party, information stored or retrieved for this purpose alone cannot usually be used to identify you.

Marketing

The technical storage or access is required to create user profiles to send advertising, or to track the user on a website or across several websites for similar marketing purposes.