The countdown is on for The British Shooting Show – book tickets online today and save on gate price!

The history of gunfit

It’s quite easy to look at a Best hammerless sidelock ejector and admire the perfection of form and function. It’s far harder to admit that the French have greatly influenced the sport of shooting and, as a result, the fit of a shotgun as we know it today.

Gunfit is a mercurial topic and far from an exact science. It provokes heated debate between different specialists in the subject, but it was barely even considered before we adopted the French habit of shooting flying birds. So let’s look at the history of gunfit and go back a few centuries.

Leading trap shooter Giovanni Pellielo has a short stock and his eye over the thumb of his grip hand

History of gun fit

The earliest ‘haile shot’ guns using their ‘villainous saltpetre’ in the Royal Armouries were likely born out of Henry VIII’s difficult relationships with his European neighbours. By the end of his life, Henry owned 41 such guns as a by-product of the pace of military invention as he modernised his army in response to the ease with which European politics descended into war.

This resulted in guns such as these being gathered from all over Europe into the English royal arsenal. They were specifically for bird hunting, though, not for military use, and guns were derided by many military types who preferred the old-fashioned certainty of a pike.

The shot was cut from lead sheets and the stock shapes were the result of the style of shooting at the time, typically at birds on the ground or on water. It simply wasn’t possible to shoot overhead birds with these guns, as the priming powder would have fallen out of the pan of a wheel lock or matchlock.

Even today, enthusiasts who tackle driven birds with their early flintlocks (and their pan covers) run certain risks. I have seen one set his hat on fire when the burning powder fell back as he took a high overhead shot. These early guns were rarely shouldered as we would a modern shotgun, many being brought to the face for an aimed shot at a static bird, so not an instinctive shot.

It wasn’t until the French aristocracy looked down their noses and decided that shooting birds on the ground was beneath them — in more ways than one — and that a good use of a servant was to get him to drive game out of coverts, that the sport of shooting flying birds began to develop and with that the shape of a gunstock.

As this fashion grew, some interested English onlookers had time on their hands while they waited in exile for the political conditions to be right for the return of their patron, Charles II, to his English throne. With the resignation of Cromwell’s ineffectual son, Richard, who inherited the title of Lord Protector but none of his father’s political, administrative or military acumen, the political and financial tide shifted in favour of these courtiers.

Stock shapes evolved from the early wheel lock guns through to the semi -pistol grip

With the restoration of Charles II and the orgy of patronage and aggrandisement that followed, they brought back with them the new fashion for shooting flying birds and no doubt some different-looking guns designed to be shouldered, not as before held under the armpit as the face came down to the stock.

The new king was less interested in matters of state than he was in his prodigious record with his mistresses and the hedonistic pleasures of sport. Hunting flying birds with muzzle-loading shotguns was on the rise to such an extent that, in 1671, new laws were issued limiting the taking of game to those with a landed income of at least £100 a year.

Semi-pistol grip

Gunstock shape

This plays a big part in the history of gunfit. To connect consistently with a flying bird, the shape of a gunstock needed to accomplish three things. First, when the stock was brought to the shoulder, it needed to enable a nobleman to hit a bird at 20 or 30 yards without any conscious correction for alignment. Secondly, it should allow the nobleman to shoot in comfort, without any bruising to either his face or his shoulder. Lastly, it should look graceful, as any fashionable, courtly pastime needed to be undertaken with a certain élan. These are broadly the three categories that still matter today in gunfit.

Guns of this early period are notably shorter-stocked than we are used to today for a variety of reasons, including that people are now generally taller and longer-limbed. As an example, Charles II struggled to disguise himself for his escape to exile because, at 6ft, he was unusually tall for the period.

Barrels of these early hunting guns were also far longer than we are used to today. An early treatise on the subject recommended a gun with a barrel 3ft (36in) in length as a good all-rounder.

The French continued to exert an influence, and in the 1730s, French sporting guns arrived in England with the addition of a second barrel beside the first. Though these early side-by-sides were derided by some, who picked out their French origin as part of “a great many other foolish things”, some British gunmakers took note.

Sixty years later, the great Joseph Manton had perfected the design and shape of the gunstock for a double-barrelled muzzle-loader for shooting flying birds. His apprentices, who included James Purdey, Thomas Boss, William Greener and Charles Lancaster, would carry on shaping French walnut (there they are again) the same way into the modern era.

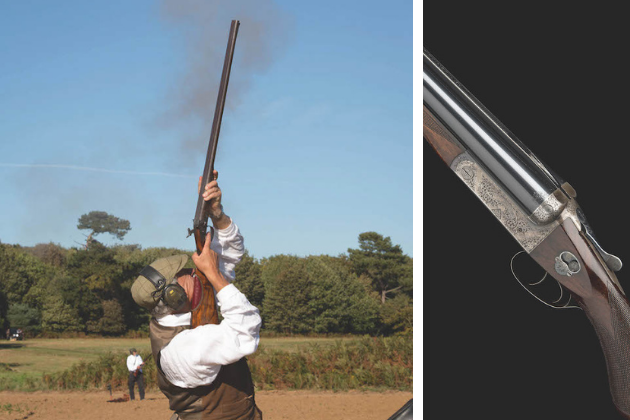

Gunfit is central to comfort and shooting technique

How to tell if your gun fits you

- Are you experiencing pain or bruising in your face, shoulder or second finger of your trigger hand?

- Practising your mount in a mirror – are you having to adjust to align your eye over the rib?

- Closed eye gun mount – mount your gun on a ceiling corner and close your eyes as you do it. Open them immediately afterwards – are you having to correct your alignment?

- Traditionally, point of impact was assessed by mounting and firing at a pattern board or sheet iwth a centre cross at 16 yards with a tight choke. Is the pattern where you want it to be?

- If you suspect any problems, engage a good shooting instructor or coach

Changing times in the history of gunfit

When another Frenchman, Casimir Lefaucheux, ushered in a whirlwind of invention with his radical patent breechloader, gunfit became more of a refined art as part of the melting pot of ideas and energy in the latter half of the 19th century.

At the end of the period, the London trade began to offer over-and-unders and existing clients were surprised to discover that the gunmakers insisted on remeasuring them for fit. The inherent stiffness of over-and-unders means they are less prone to muzzle-flip so they shoot higher than a side-by-side. To counteract this, stockers would increase what they then termed ‘bend’, more commonly ‘drop at comb’ and ‘drop at heel’ these days.

Another development in the history of gunfit came out of high-stakes shooting matches behind the Casino de Monte Carlo. Fortunes were made and lost in the live pigeon shooting ring, the forerunner of trap shooting.

Developed by Webley & Scott, a Monte Carlo stock has its comb raised higher and a dip down to the heel of the buttpad. It enabled the gun to come to the cheek quicker as the pigeon was released, allowing an earlier and closer shot to be taken, with a higher chance of success. When this translated into winning big cash, competitors asked their gunmakers to provide these stock shapes.

At about the same time, Edward, Prince of Wales, was making a specific request of James Purdey & Sons to provide a more open radiused grip for his side-by-sides, so that his hand could stay located on the grip with the wrist not cocked, as with a full pistol grip. His style of shooting was to move his front hand depending on the bird.

Grip shape is one of those aspects that has become more prominent in modern gunfit, especially with modern reliable single triggers that dominate on over-and-unders where there is no need for the hand to move between the first and second shot.

There is a modern trend towards buttplates with almost no pitch (the difference in angle between the heel and toe) or shape to them (compare a Beretta pad with a Longthorne). I don’t believe this is a positive step, but as the history of gunfit shows, it is a moveable feast.

Giovanni Pellielo, one of the best trap shooters in the world, has what many would consider too short a stock and his eye over the thumb of his grip hand. Conversely, Kimberly Rhode, the American double trap and skeet shooter, appears to prefer a stock that looks far too long, but with three Olympic gold medals, no one can deny that it works for her.

Personal style

Looking at the history of gunfit, some say that the stocks from the gunmakers of old are not suitable in the modern era. For me, it is hard to ignore the time, effort and expertise from successive generations of pre-war gunmakers.

Once you have established a personal style of shooting, gunfit is entirely dependent on what is comfortable for you, your body shape and the type of shooting in which you are engaged.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Shooting Times & Country

Discover the ultimate companion for field sports enthusiasts with Shooting Times & Country Magazine, the UK’s leading weekly publication that has been at the forefront of shooting culture since 1882. Subscribers gain access to expert tips, comprehensive gear reviews, seasonal advice and a vibrant community of like-minded shooters.

Save on shop price when you subscribe with weekly issues featuring in-depth articles on gundog training, exclusive member offers and access to the digital back issue library. A Shooting Times & Country subscription is more than a magazine, don’t just read about the countryside; immerse yourself in its most authoritative and engaging publication.