The countdown is on for The British Shooting Show – book tickets online today and save on gate price!

What does a ‘best’ gun actually mean?

A recent sale elicited a good question and disinterred an old discussion. The sale concerned a J. Blanch & Son sidelock ejector made in 1903. We know it was made then because the engraver, probably the great Harry Kell, had carved that date, in Roman numerals, on the guard. Toby Barclay, who knows more about Blanch than anyone I know, was certain Blanch only engraved this on his best gun selection.

The question a customer asked was this: “Is the Blanch actually a best gun? Cyril Adams once wrote that best guns cannot have through lumps, which the Blanch has.”

More recently, while I was shooting with Purdey chairman Dan Jago, he referred to all of Purdey’s current line-up as ‘best guns’. That, of course, covers their much-loved Beesley self-opener and the beautiful Woodward over-and-under. It also claims ‘best’ status for the more recently introduced trigger-plate over-and-under models.

For Diggory, a ‘best gun’ is a work of art

What is a best gun?

What then, is a ‘best gun’ in 2022? To answer the question, we have to examine some first principles and glance back into history. Best guns have been a benchmark for the quality demanded by the British aristocracy since the days of Joseph Manton. The term ‘best’ traditionally referred to a bespoke gun made to the highest quality in every respect, regardless of time or cost of manufacture. (Read English guns – are they still the best?)

Famous names

When John Robertson touted Boss as “builders of best guns only” in 1900, he sold only sidelocks and over-and-unders. There was a demand for cheaper boxlocks but he refused to put the name ‘Boss & Co’ on these; instead using ‘John Robertson’, with the Boss address on the rib.

Holland & Holland, Rigby and Purdey, like most other gunmakers, sold a range of models at various prices. Just because you have a Purdey, it does not mean you have a ‘best gun’ necessarily. It could be a ‘B’ grade. If you have a Holland & Holland, it could be a Badminton or a Dominion; neither are best guns. A Rigby D-quality double rifle is by no means best. All these guns and rifles are very well made and mechanically excellent, but they are not ‘best’. (Read can I buy a Purdey or a Holland & Holland on a budget?)

Purdey in Mayfair

Simply bearing a famous name does not make a best gun. To claim so is historically and factually inaccurate. However, some makers reliably catered to the top of the market, while others were less expensive; William Powell’s best gun in 1932 cost £95, Purdey’s cost 120 guineas, as did E.J. Churchill’s, and Boss charged 130 guineas. Was Powell’s best gun truly best objectively or just the best he made at the time?

The long room at Purdey

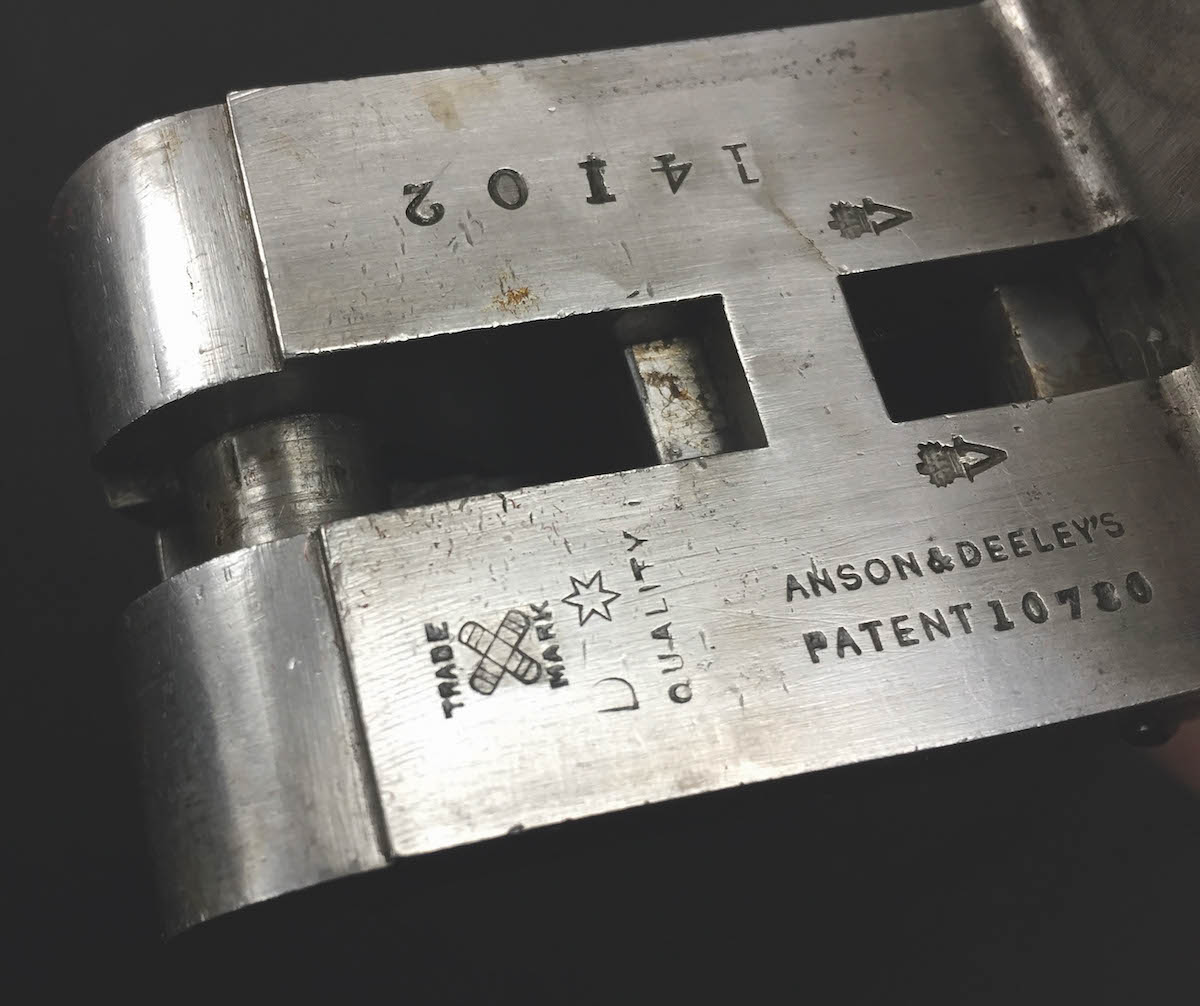

I mentioned earlier that Robertson eschewed boxlocks from his ‘best’ inventory. Does that mean boxlocks cannot be best guns? Again, history can answer. Best guns were certainly made before 1875 (when the Anson & Deeley boxlock arrived) and therefore, before 1880 (when Purdey started building the Beesley self-opener). So, the best gun concept was established well before hammerless guns were the norm.

Not all Purdeys or Holland & Hollands are ‘best guns’ they sell a range of models at various prices

Action type

‘Best’ hammerguns undoubtedly exist, even ‘best’ muzzle-loaders, so why not any other mechanism? In Scotland, John Dickson and James MacNaughton were very much orientated towards best guns when they began producing the trigger-plate models upon which they built their fame. MacNaughton’s Edinburgh gun and Dickson’s ‘round action’ are invariably of best quality.

As for boxlocks, W.W. Greener considered his version of the principle (the 1880 Facile Princeps) superior to the best sidelocks of the day. A Greener G gun is qualitatively every bit the best gun that a Holland & Holland Royal is.

Westley Richards, originators of the Anson & Deeley action, made a lot of these as best guns and refined them more with the introduction of the 1897 patent hand-detachable-lock version, which is still made to ‘best’ standards. We can, therefore, assert that action type is not a measure of a best gun.

This old Purdey boxlock can be seen to be stamped with ‘D-Quality’ – definitely not a ‘best’ model

As for niceties regarding details, we can certainly make a case for the evolution of a best gun gravitating towards certain practices. These became conventions and then led to the kind of assertion attributed to Cyril Adams — “best guns do not have through lumps” — and another, often-heard, claim that “best sidelocks are stocked to the fences”.These claims stem from practices that were adopted. However, they do not apply to guns made earlier, before the stylistic convention became established.

Time-specific

Well after Boss claimed to build “best guns only”, the firm delivered sidelocks with shouldered actions (not “stocked to the fences” in the style of a Purdey). The same observation can be made of the first model Holland & Holland Royal, which not only had a shouldered action but dipped-edge lockplates as well.

These examples debunk the claim that to be ‘best’, a gun has to stick to a set of stylistic criteria applied as if they were universal. They were, actually, very time-specific. What we observe as a convention applied to the best guns of 1935 we cannot demand of those made in 1910. They are not, however, necessarily bad clues for which to look.

This Joseph Manton was converted by S.&C. Smith in 1843 – chosen as a ‘best’ gunmaker of the time

Best hammerguns usually do not have through lumps, best sidelocks of the post World War I era do not usually have shouldered actions, and most boxlocks are not best guns. So, there is some truth in these claims but the devil, as always, is in the detail.

To be ‘best’, every stage of production has to be of the highest standard: both workmanship and materials. If it is not the work of the best craftsmen, it probably won’t be a best gun. If it is made from materials that were not the best then available, it probably won’t be a best gun.

This observation precludes any gun made with inferior parts and materials and then disguised with finish. We saw numerous examples in the 1970s and 1980s of British firms buying Spanish barrelled-actions, and stocking, engraving and finishing them in the UK. They will never be best guns because they started life with a compromise to save costs.

The quality of some hammer guns is apparent when the locks come off – best work stands out.

Gunmakers often produced a best gun for their shooting customers, but created even more expensive ‘exhibition’ or ‘presentation’ grade guns. These went beyond what would be considered the best that gunmakers could produce for sporting purposes. These higher-finish guns might compromise practicality for beauty, such as wood so well figured it lacked the strength of that fitted to a best gun intended for heavy use in the coverts. Best guns had to be fit for purpose.

For some, the amount of machine work involved in making a gun is a factor. A Fabbri, for example, is made with very little bench work, yet it is more expensive than the output of all London’s best makers. Is a Fabbri a best gun?

Gunmakers have always used machines. Lathes, mills, treadle power, steam power, electric power; whatever made the work easier and faster. Today, we just have more sophisticated machinery. So, it would be unfair to demand that to be a best gun, no machines are allowed in the production process. It has never been so. (Read what’s best a family heirloom or a new shotgun? )

Subjective artistry

A shooting friend reflected: “I have had Fabbris and they are beautiful, but they have no soul.” Soul, whatever that is, is built into a gun by the hands of the craftsmen who build it. Beauty is not objective perfection, but subjective artistry. In guns, it is a blend of artistry and engineering.

The beauty inherent in a best gun is hard to decipher. In the truly best it is undeniably present but it cannot be measured. Machines cannot impart that. We are close to a time in which machines can spit out every part necessary to build a traditional London gun so accurately that, with a simple assembly process, you will have a fully working example of a 19th century masterpiece.

Laser engraving, laser chequering and synthetic finishing may one day be the equal of the work any craftsman can deliver. But these will not be best guns. They will be facsimilies of best guns.

A gun built by the hands very skilled men, working to the best of their abilities with the finest materials, creating a work of art that functions perfectly, comes to life in the hands of its wielder and develops more character as it ages: that is a best gun. Now, try to convince me otherwise.

Related Articles

Get the latest news delivered direct to your door

Subscribe to Shooting Times & Country

Discover the ultimate companion for field sports enthusiasts with Shooting Times & Country Magazine, the UK’s leading weekly publication that has been at the forefront of shooting culture since 1882. Subscribers gain access to expert tips, comprehensive gear reviews, seasonal advice and a vibrant community of like-minded shooters.

Save on shop price when you subscribe with weekly issues featuring in-depth articles on gundog training, exclusive member offers and access to the digital back issue library. A Shooting Times & Country subscription is more than a magazine, don’t just read about the countryside; immerse yourself in its most authoritative and engaging publication.